- Home

- Susan Hill

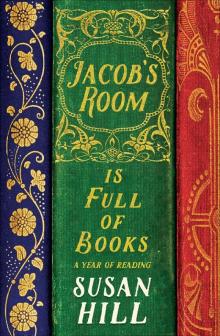

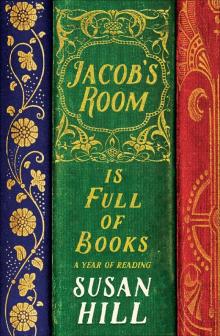

Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books Read online

Jacob’s Room Is

Full of Books

Susan Hill has been awarded a CBE for her services to literature. Author of the Simon Serrailler crime series and numerous other novels, her literary memoir Howard's End is on the Landing and the ghost stories The Man In The Picture, The Small Hand, Dolly and The Travelling Bag are all published by Profile.

ALSO BY SUSAN HILL

GHOST STORIES

The Small Hand

The Woman in Black

Dolly

The Man in the Picture

The Travelling Bag and Other Ghostly Stories

NOVELS

Strange Meeting

In the Springtime of the Year

I’m the King of the Castle

SHORT STORIES

The Boy who Taught the Beekeeper to Read

and other Stories

CRIME NOVELS

The Various Haunts of Men

The Pure in Heart

The Risk of Darkness

The Vows of Silence

The Shadows in the Street

NON-FiCTION

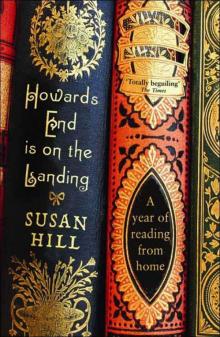

Howards End is on the Landing

Jacob’s Room Is

Full of Books

Susan Hill

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright © Susan Hill, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84765 919 4

For my friend Lynne Hatwell

aka Dove Grey Reader

Who has read more books than me – and she’s younger

JANUARY

NEW YEAR NON-WEATHER. Wet. Dank. Grey. Chilly but not winter cold.

And people have made me cross. I have never ‘done’ New Year. Time is seamless. Months, days, weeks, years are artificial, manmade things, so what are we celebrating? Personal choice, of course, and I don’t in the least mind retiring to bed at ten p.m. with a good book and hearing the fireworks exploding all round me a couple of hours later. But going out this morning, by the ford – that beautiful, healing spot where the river runs shallow and clear over grey stones and one sees kingfishers – just there, fireworks have been let off on the grassy bank, and all the detritus of cardboard tubes and wooden sticks and burnt-out plastic has been left where it has fallen. Never mind that nobody bothered to pick anything up – they probably didn’t even notice. None of it looks very bio-degradable.

I am not a loud fusser-about-litter. I know I ought to join picking-up parties but somehow I never do. But, like discarded plastic hamburger boxes and Coke cans, the firework mess is a mess too far.

I FIND A LADYBIRD, living on my bedside table. I could do with some decoration, the house looks so bare after Christmas. Is this the only insect absolutely everybody loves? Would we find it so charming if it had, say, a sludge green back instead of a scarlet patent leather one? Is it the spots that do it? What if it were transparent?

Now, a Red Admiral butterfly has emerged from some crevice and is fluttering round the room, having come in on the logs and hatched in the warmth. It pats the windowpane softly. But it is far better off staying inside. It is light and warm in here and it might live for days. If I let it out into the bitterly cold night, it will die in minutes.

Vladimir Nabokov was a butterfly expert. If an author’s full biography is not generally of interest in separation from the work, sometimes the odd incongruous fact may amuse us and add an extra dimension to the writing as well. Nabokov was a world-renowned lepidopterist. T. S. Eliot worked for years in a bank. Both those facts seem exactly right.

And Noel Coward spent his last weeks reading E. Nesbit. The Story of the Treasure Seekers. Five Children and It. The Railway Children.

Who knew?

Freezing wet December, then …

Bloody January again!

I ALWAYS THINK that’s by Joyce Grenfell, until I check and as usual find that it is by Flanders and Swann. Theirs was the sort of humour beloved of old-fashioned vicars and their wives. They roared at ‘Mud, mud, glorious mud’, they hooted at ‘And ’twas on a Monday morning that the gas man came to call’. They rocked at ‘I’m a gnu’ and when the line (after a pause ) ‘A GN-OTHER GNU’ came, they laughed until their sides ached and the tears ran down their cheeks. Vicarly humour is very simple. Flanders and Swann, with their impeccable timing and songs that brought the small struggles of everyday domestic life into focus, were a great partnership. But they haven’t really stood the test and taste of time, though ‘I once had a whim, and I had to obey it/To buy a French horn in a second-hand shop’ – sung to the tune of Mozart’s Horn Concerto – is still delightfully entertaining.

Massed clergy loved Joyce Grenfell, too. So did I. But have her slightly arch, slightly coy way of singing and doing monologues dated, too? Quite a few of them have, but ‘Old Girls’ School Reunion’ comes up fresh every time you hear it, because it is still so true – or it has been in my experience. ‘Ah, Ma’mselle … c’est très gentil de vous voir,’ spoken in the perfect Franglais accent. ‘Remember me? Lumpy Latimer.’

She brought that, and so many other light-hearted pieces, to vivid life because there was a touch of the old girl about Joyce herself. The fact that she was a little goofy meant that she could play a police sergeant posing as a games mistress in the wondrous film The Belles of St Trinian’s, wearing a panama hat and brandishing a hockey stick, to perfection.

Her one-woman shows, Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure and several others, in which she always had some amusing friends as guests, were hugely popular with the middle-aged and elderly middle classes and, of course, the vicars. She took people off and she poked gentle fun, but there was not a breath of malice in them.

I can sing ‘Stately as a Galleon’ from beginning to end. I wonder how many others are left who can do that. But Joyce Grenfell is perhaps best remembered for her infant school teacher monologue – all infant school teachers sound like her – in which she utters the immortal, perfectly inflected line, ‘George … Don’t do that.’

Happy days, when vicars and the rest were satisfied by such innocent, simple pleasures as Flanders and Swann and Joyce Grenfell. Satire, The Establishment club, That Was The Week That Was and the black humour songs of Tom Lehrer were the beginning of the end for all that.

DARK WALK UP THE LANE, with dog, cat and torch. Two tawny owls fly up in alarm from the oak trees. A bit further on, one barn owl silently glides from the field. There is a whole world out there living its own life without reference to us.

It is often said that mankind needs a faith if the world is to be improved. In fact, unless the faith is vigilantly and regularly checked by a sense of man’s fallibility it is likely to make the world worse. From Torquemada to Robespierre and Hitler, the men who have made mankind suffer the most have been inspired to do so by a strong faith – so strong that it led them to think their crimes were acts of virtue, necessary to help them achieve their aim, which was to build some sort of ideal kingdom on earth.

But, as we have been told on very good authority, the Kingdom of Heaven is not of this world. Those who think they can est

ablish it here are more likely to create a hell on earth.

I found this, written down on a piece of paper inside a file. It’s from David Cecil’s Library Looking-Glass and seems entirely true and pertinent.

WHEN I WAS SEVEN, I got pocket money for the first time – not a lot, but enough to buy my weekly copy of the Beano, so I was happy. When my daughter Jess was the same age, she got enough to buy some penny sweets every Saturday – and her copy of the Beano. The routine was always the same. She settled back in the big, reclining armchair. She lined her sweets up carefully along the arms, in order of eating. And then she reclined and opened her comic. Once, as she did so, I heard her sigh, ‘Ahhhhh. This is the life, readers.’

Now, at roughly the same age, my step-great-nephew, Ollie, has just been given an annual subscription to the Beano for Christmas.

What is it about comics? Why did the parents of my generation of children so disapprove of them? Maybe some still do, but not many, because now we have graphic books – sometimes original, sometimes re-tellings of Shakespeare and other classics – and they seem quite acceptable.

I can’t read anything in strip form now, or at least nothing longer than the Snipcock & Tweed cartoon in Private Eye, but somehow I can still manage the Beano Annual, which I am given every year.

Was it the anarchic, subversive element of the Bash Street Kids and other low-life of which our parents so disapproved? Was it all the joyous KERPOW!!!!! SPLAT!!! and ZOOOOOOM!!!!! which emboldened the pages? A bit of both and more, I suspect. But I think a mild form of anarchy should prevail among the under-tens. Via the Beano and the like, they see that kids can mock and deride and misbehave and cause mayhem and still survive and thrive, and that AUTHORITY does not always have the last word. It is all good old-fashioned fun. I sometimes wonder what Ollie makes of teachers wearing mortarboards, though.

I once interviewed a representative from the Beano’s publisher, D. C. Thompson, on a Radio 4 book programme. It was harder to get hold of him than someone from MI5. They’re a cunning lot up there in Dundee, they play their comic cards very close to their chests. But after extracting drops of blood from the Scots stone, I got him to reveal that they were creating a new character, to go alongside Gnasher. Now, this had involved two years or more of market surveys, creative conferences, design meetings and Lord knows what else. A new character is a Big Deal in the comic world and it can’t be seen to fail. It has to stand the test of the next twenty-five years of readers – at least.

But finally, finally, they had come up with Gnasher’s little brother, Gnipper. And the man from the Beano said, ‘Because he goes gnip, gnip, gnip.’ And he emitted a Dundee-an chuckle and with that chuckle, which was only a tad short of gleeful, I realised that the grown-up men who create the Beano weekly for their paid work are just a bunch of 9-year-old boys. It was very heartening.

SPENDING A QUIET WEEK working in a rented Cotswold cottage. As usual, there are books on the shelves left behind by previous renters and here is Embers by the Hungarian writer Sandor Marai, one of those books that sprang fully formed out of Zeus’s head to become, when it was re-published in English a few years ago, the novel everyone was reading. Publishers call them ‘word of mouth’ books but they are more – they are word of the internet, the online book groups, the seen-a-fellow-commuter-reading-it books. John Williams’ Stoner was another such. Josephine Hart sent me a copy one Christmas – I had never heard of it and nor had many other people, but she was the kind of generous book-lover who just bought fifty copies of something she liked and sent them to friends. That is enough to start a ball rolling, but only if all other things are equal – meaning, not only must said book be exceptionally good, but it must have the X factor which makes it appeal to a wide variety of readers, crossing sexes, ages, reading types. Stoner did that. It had a universal appeal. So did Embers. All manner of people loved them both, not just those who prefer crime fiction, or love stories, or sagas, or books in translation, or very literary fiction, or books about animals, or historical novels, or … The formula for word-of-mouth bestsellers is a mystery. Everyone wants it, everyone would like to bottle it. Nobody ever has and when they try, they are always doomed to fail and get their fingers burned.

I pick up Embers to read again and, after a few chapters, realise that the same thing could happen to this a second time. It is a beautiful novel. It has lost none of its attraction, it has not ‘dated’ or been done again but better. Indeed, I think that is one of the tests of this sort of book – that it is a one-off. It is not ‘If you liked this you will enjoy that …’ It is just itself. There are as many novels about love as there are pebbles on a beach. But how many are there about friendship? Yes, friendship is a form of love, but I mean in its purest, simplest form – friendship. I can think of some children’s books about friendship – Tove Jansson’s Finn Family Moomintroll series, for a start. There are many about friendship between a human and an animal, too. But friendship as friendship?

Sometimes, one short paragraph can reveal that you have in your hands a novel by a great writer:

It is the kind of idea that comes later to most people. Decades pass, one walks through a darkened room in which someone has died, and suddenly one recalls long forgotten words and the roar of the sea.

(Embers)

The message, if not the rule, is always to leave behind on the shelves the books you have enjoyed yourself when on holiday, for someone else to find. Perhaps that’s another way a slow-burner overtakes the pack to become a bestseller.

I HAD A KINDLE. I read books on it for maybe six months, and then I stopped and went back to printed books. I did not do it for any reasons whatsoever other than organic ones. I prefer holding a real book, turning paper pages over, turning them back, bending the spine, dog-earing the corners, underlining in pencil, making margin notes in pen. My taste. I can see all of the arguments for the convenience of the e-reader but I like to have a physical relationship with my books.

There is more, though. I gave up reading on a Kindle because I found I was not taking the words and their meaning in, as I do those in a printed book. They went in through my eyes but seemed to glide off into some underworld, without touching my brain, memory or imagination, let alone making any permanent mark there. I was puzzled by this, until I learned that if we use an e-reader or a laptop before going to sleep, our brains are affected so that we are more likely to sleep badly. It is something to do with the blue light. I’ve forgotten. The e-reader is cold, and what I mean by that I cannot put into words or explain, I can only feel that it is the right way of describing the experience, as against the warmth of a physical book.

Cold room, warm bed, good book. But I think whatever this blue light thing is, it is responsible for making the printed word slide past the brain on its way to oblivion.

I do not travel much and never go on long-haul flights. Friends who do, popping over to New Zealand as I might pop over the road, can take a dozen, or a hundred, long tomes loaded on to one small, light e-reader. And I can see the charm and convenience of that. Even if they never sleep and return home with no memory whatsoever of what they have read.

IS LISTENING TO an audio book the same as reading it? In the most obvious sense, no. I don’t listen to them myself. I prefer to read in silence, and to be able to go back and over a paragraph again. I want to hear the voice of a narrator sound as I imagine them to sound. But if I were blind, of course I would listen to them. My great uncle Leonard, who had been blind since he was fourteen, had Books for the Blind delivered to him every other week. They were heavy leather boxes containing large, cumbersome records and his pleasure in listening to Churchill’s war-time speeches, or J. B. Priestley reading his own essays, was very great. He sat in his armchair of an evening, fingers making a steeple in front of his face, and listened for two or three hours. My great aunt took him a cup of tea and a biscuit at half time, and at ten o’clock he went to bed. I had gone to my own several hours before, of course, but I lay listening for as lo

ng as I could possibly stay awake, hearing the growl of Winston Churchill intoning through the wall. The books were provided free and delivered and collected free, courtesy of Libraries for the Blind. It was a lifeline.

Now, people cycling and running, ironing and train travelling, appear to be listening to audio books through headphones – though I am sure more of them listen to pop music – and the crime writer Val McDermid listens to them all the time while she is pounding a treadmill. But, for me, listening still loses out to the reader’s silent progress along the lines, and so down the sentences, the paragraphs. I also find that the reader’s voice gets in the way, or it is a voice I don’t like, or worse, find seriously grating. But audio books are selling as never before, so I must be wrong. No, not wrong. Just different. Besides, most sighted people I know who sometimes listen to audio books also read books to themselves.

The BBC gave us some iconic readings of famous books. Whoever chose Martin Jarvis to read the Just William books, and Alan Bennett to read Winnie the Pooh, was a casting genius. Ah, Just William. So many adults listened to those readings on Radio 4. So many of us remember William, his mate Ginger, his sister Ethel and her soppy fiancé Robert, and the dreadful Violet Elizabeth Bott, who would thcream and thcream until she was thick. A friend’s daughter recently called her new baby Violet Elizabeth. She had no idea …

MEANWHILE, THE TEMPERATURE has dropped to minus 7, the fire is lit and I am re-reading May Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude. I have never known such a self-regarding, self-indulgent author. Yet isn’t writing a journal bound to be an outpouring of self? No. I can think of so many diaries and journals that of course are about the writer and her or his life and experiences, feelings, thoughts, beliefs, friends … but which do not seem self-centred in this way. May Sarton was, by all accounts including her own, the most infuriating woman to know. She believed she was a major poet, that poetry was her form. She was wrong. She thought she was a fine novelist. She was an OK one. How harsh this is. But she is dead and cannot read me.

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing