- Home

- Susan Hill

Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Read online

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Also by Susan Hill

Title Page

Preface

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Postscript

Copyright

About the Book

Orphaned at the age of five and sent away from England to Africa, Sir James Monmouth has spent most of his life travelling, following in the footsteps of his childhood hero, the explorer Conrad Vane. He returns to England one dark and rainy night with the intention of discovering more, not just about himself, but the early life of the explorer. Warned against following this path, Sir James becomes yet more determined to unravel the mysteries of the past – but who is the mysterious little boy who haunts his every step, and why can only he hear the chilling scream and the desperate sobbing?

About the Author

Susan Hill’s novels and short stories have won the Whitbread, Somerset Maugham and John Llewellyn Rhys awards and been shortlisted for the Booker Prize. She is the author of over forty books, including the four previous Serrailler crime novels, The Various Haunts of Men, The Pure in Heart, The Risk of Darkness and The Vows of Silence. Her most recent novel is A Kind Man. The play adapted from her famous ghost story, The Woman in Black, has been running on the West End stage since 1989.

Susan Hill was born in Scarborough and educated at King’s College, London. She is married to the Shakespeare scholar, Stanley Wells, and they have two daughters. She lives in Gloucestershire, where she runs her own small publishing company, Long Barn Books.

Susan Hill’s website is www.susan-hill.com

ALSO BY SUSAN HILL

Featuring Simon Serrailler

The Various Haunts of Men

The Pure in Heart

The Risk of Darkness

The Vows of Silence

Fiction

Gentlemen and Ladies

A Change for the Better

I’m the King of the Castle

The Albatross and Other Stories

Strange Meeting

The Bird of Night

A Bit of Singing and Dancing

In the Springtime of the Year

Mrs de Winter

The Woman in Black

Air and Angels

The Service of Clouds

The Boy Who Taught the Beekeeper to Read

The Man in the Picture

The Beacon

The Small Hand

A Kind Man

Non-Fiction

The Magic Apple Tree

Family

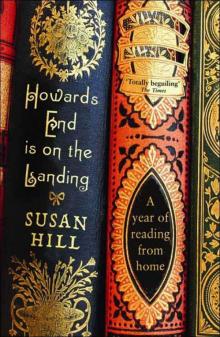

Howards End is on the Landing

Children’s Books

The Battle for Gullywith

One Night at a Time

The Glass Angels

Can it be True?

SUSAN HILL

The Mist in the

Mirror

PREFACE

to Sir James Monmouth’s

manuscript

London, and the library of my club, towards the end of an afternoon in late November, that bleak, dispiriting time of year when the golden Indian summer days that lingered on through October seem long gone, and it is yet too early to feel the approaching cheer of Christmas.

Outside in the streets the air was raw and a light mizzle greased the pavements, and had chilled my face and damped the sleeves of my coat.

But I had made the best of my walk down through the narrow streets and alleys of Covent Garden, dodging between stalls and barrows, glimpsing the interior of the Halls, lit like glowing treasure caverns within, and so coming briskly towards Pall Mall.

And now, I paused at the doorway of that handsome room, and for a few seconds looked with quiet appreciation on the welcoming, untroubled scene.

The lamps were lit, and a good fire crackled in the great stone fireplace. There was a discreet chink of china, the brightness of silver teapot and muffin cover, the comforting smell mingled of steaming hot water, toast and a little sweet tobacco.

The dreech weather had drawn in a few more than usual at this time of day but I saw no close acquaintance and I had a mind to drink a quiet pot of tea and glance at the early edition of the evening paper, content in my own company. Nevertheless, I responded readily enough to the nod of the man seated a little apart across the room in one of the deep recesses between reading desks, for he always cut a melancholy figure and my conscience was pricked by seeing him alone.

‘Sir James …’ I sank into the depths of the old mahogany leather. Behind us, the heavy curtains were still undrawn and I could see the street lamps haloed in the thin mist.

‘The fag end of a pretty miserable day.’

Sir James Monmouth nodded. He was a reserved, still handsome man, neatly tucked into himself. A lawyer? A civil servant? I had no idea, but he always made himself agreeable to the younger Members in a modest, unobtrusive way, and what I knew of him, I liked.

‘Still,’ I said cheerfully, as the tea arrived, and I spied the jar of anchovy paste beside the buttered toast, ‘I had an excellent walk. I confess to loving the streets of London no matter the weather.’

‘Ah,’ Sir James said reflectively, ‘the London streets. Yes. A man may walk for many an hour through them.’ He settled more deeply into his armchair, leaning back so that his face was in shadow.

‘Of course, it is a fine thing so long as one has a refuge such as this at the end of an afternoon – lights, a good fire, congenial company … tea and toast.’

‘Yes,’ he replied, after a pause, ‘a refuge indeed. I have been glad to find it so.’

‘You are generally here, Sir James.’

‘Yes. Yes, generally here. I pray I may always be so, for this place is home to me now, and friends and family too.’

Something in his tone affected me, so that I felt a sudden unease, and, rather too heartily, pressed him to have a slice of the excellent toast. But he waved it politely away and, at the same moment, a couple of my friends entered and came across to join us, and the mood was lifted.

‘We have been hearing from Sideham,’ – Sideham was the Senior Porter – ‘about an apparent sighting of a guest wing ghost!’

‘I had no idea there was such a thing,’ I said. ‘A headless guardsman?’

Ffoulkes snorted with laughter, and at once heads were turned in our direction, there was some reproving clicking of tongues, and we became chastened and quiet, and the library settled back into its customary hush.

But the subject of ghosts was raised again as we sat in the smoking room after dinner and, over glasses and pipes, speculated on various theories and philosophies to do with spectres, the afterlife and worlds beyond the grave. The story of the Club Ghost was told – and reckoned to be a feeble and unremarkable one. And though we encouraged one another mildly, trying to set the mood, no good and gripping original tale was produced by any of us.

‘There’s many an excellent ghost story printed,’ Ffoulkes said at last, ‘we had better leave the telling of them to the professionals.’

And so the subject dropped, and we went on to talk of quite other matters.

The party broke up just before midnight, and I was crossing the hall towards the cloakroom when I turned, hearing a step immediately behind me.

‘You are t

aking a cab, I daresay?’ Sir James Monmouth spoke with a certain diffidence and hesitation.

‘No, no. It is but half a mile to my rooms. I shall walk.’

‘Then – if I may keep you company for a short step?’

‘By all means. Like me, you feel the need of a breath of air before turning in.’

He did not reply, only went to wait beside the entrance doors. I was quick to don my coat, and we left together.

There was still the same chill mist, which caught the back of the throat and bore city smoke and London’s river mingled on its breath.

On the corner, the chestnut brazier glowed faintly, though the seller had packed up and gone an hour or more since.

None were about. The tall, stuccoed buildings loomed, blank-eyed, above us.

For a moment or two we walked without speaking, but I was sure Sir James had not, in fact, come out with me simply in order to stretch his legs after an evening seated indoors. His very silence had a tension about it.

We reached the next corner where a solitary cab waited under the lamp.

My companion stopped.

‘I will drop back now.’

‘Well, then, I will bid you goodnight, Sir James.’

‘A moment …’ He hesitated. His beak-nosed face was gaunt, and skull-like beneath the thin hair. I realised that he was much older than I had supposed.

‘I could not help but overhear, after dinner … your conversation in the smoking room.’

‘Oh, that was idle enough talk. They are amiable fellows.’

‘But you yourself appeared – more serious.’

‘I confess that the subject has always held an interest for me.’

‘You – believe?’

‘Believe? Oh, as to that …’ I made a dismissive gesture. The topic was not one I wanted to raise again, in that late, silent street.

‘I have … a story. It is in my possession … which perhaps you might care to read.’

‘A true story? Or a fiction? You are an author, Sir James?’

‘No, no. It is merely an account of certain – events.’

He lightened his tone abruptly. ‘At least, it may pass an idle hour, when next you have one.’

Just then footsteps began to be heard, at the far end of the street. Sir James turned his head quickly, and peered through the murk. Then, abruptly, his hand shot out and he clutched my arm. ‘I beg you,’ he said in a low, urgent voice, ‘read it!’

The clocks of London began to chime the hour.

It was several days before I was at the club again. Business matters took me north and from there I went directly home to Norfolk, where I relaxed by my own fireside, surrounded by my loving, happy family. Young Giles had a new labrador pup which diverted us all a good deal, and Ann was patiently walking Eliza, who was barely three, up and down the yard and across the paddock on her Shetland pony. I had an excellent day’s shooting in the foulest weather and returned home with a decent bag, and muddy breeches, happy as a lark.

I never found it easy to make the transition between Foldingay and my quasi-bachelor existence in Town; for an evening or half a day I felt ill at ease, with a foot in each camp and my mind in neither, and I generally called in at the club for a couple of hours to help ease me back.

It was near to nine on that Monday evening when I came in through the swing doors, to be greeted by Sideham.

‘One moment if you please, sir, I have a package for you entrusted to my keeping.’

‘From the Registered post?’ I was surprised. I receive little mail at the club as a rule, save the usual circulars.

‘No, sir, it was given to me by Sir James Monmouth.’

‘Ah yes.’

Our conversation, and Monmouth’s curious behaviour that night, came clearly back to mind – though I had completely forgotten it in the time between. I recalled the empty, silent street and his abrupt change of demeanour, the panic, the fear – I was not sure exactly what it had been, in his eyes and voice.

‘I wonder he did not give it to me himself,’ I said, as Sideham handed over a packet securely wrapped in brown paper and string.’

‘Sir James has gone away for a few days, sir.’

I was surprised. The old man was, as he had said to me, ‘generally here’, ensconced in one corner or other of the place. But perhaps he felt the need for an occasional change of scene, and I thought no more about the matter, only put the packet with my coat and went in to enjoy a whisky and soda.

I spoke to no one, and after a browse through a pile of sporting periodicals, my eyes felt heavy enough to prompt me to think of making for the set of rooms off Piccadilly that answered for home. On the way out, I picked up Sir James’s parcel, but had no thought of so much as opening the wrappings that night. I think I had a vague notion that I would take it down to the country with me the following Friday.

But the walk through a very cold night, under a sky bright with stars, stirred me fully awake again, and having nothing else better to do, and not wanting to turn in, only to be tossing for hours in bed, I decided to glance at the first pages of what turned out to be a trio of quarto-sized notebooks, bound in plain black leather. The manuscript was hand-written in a neat, elegant script, as easily legible, once my eye became familiar with it, as any printed book.

I settled into my chair, turning off all the lights save for one, shaded lamp beside me. I suppose that I intended to read for an hour at most, expecting drowsiness to overtake me again, but I became so engrossed in the story that unfolded before me that I rapidly forgot all thought of the time, or my present surroundings.

A bleak London dawn, seeping in around the edges of the curtains, found me still in my armchair, the finished manuscript fallen into my lap, and I into a fitful, dream-haunted, uneasy sleep.

Sir James Monmouth’s Story

CHAPTER ONE

Rain, rain all day, all evening, all night, pouring autumn rain. Out in the country, over field and fen and moorland, sweet-smelling rain, borne on the wind. Rain in London, rolling along gutters, gurgling down drains. Street lamps blurred by rain. A policeman walking by in a cape, rain gleaming silver on its shoulders. Rain bouncing on roofs and pavements, soft rain falling secretly in woodland and on dark heath. Rain on London’s river, and slanting among the sheds, wharves and quays. Rain on suburban gardens, dense with laurel and rhododendron. Rain from north to south and from east to west, as though it had never rained until now, and now might never stop.

Rain on all the silent streets and squares, alleys and courts, gardens and churchyards and stone steps and nooks and crannies of the city.

Rain. London. The back end of the year.

But to me it was delightful and infinitely strange. There had been no such rain in Africa, India, the Far East, those countries in which I had spent as much of my life as I could remember. There had been only heat and dryness for month after month, followed abruptly by monsoon, when the sky gathered and then burst like a boil and sheets of rain deluged the earth, turning it to mud, roaring like a yellow river, hot, thunderous rain that made the air sweat and steam. Rain that beat down upon the world like a mad thing and then ceased, leaving only debris in its wake.

I had heard occasional visitors from England speak of this blessed, steady, gentle rain, and at such times, a faint half-memory, like the shadow left by a dream, stirred, and came almost to the surface of my consciousness, before drifting out of reach again. And now I was here, alone in that London rain, in the autumn of my fortieth year.

My ship had docked earlier that day. My fellow passengers had crowded to the rail to watch our progress towards land and the first sight of those loved ones who awaited them. But I, who knew no one, and had no friends or family to greet me, had stayed back, half curious, half afraid, and full of a sudden fondness for the ship that had been my home for the past weeks. For I had no other now. The east was behind me, my life there over. Although I had certain vague plans, and a task I had more or less set myself, the future, and thi

s England, were unknown.

The ship’s siren boomed, and was answered from onshore. Hats went up into the air.

I turned then and gazed back down the long dark ribbon of London’s river that led away to sea, and felt for that moment utterly dejected, and as bleak-spirited and lonely as I had felt in my life.

My story up to that date may be told briefly enough. I knew only that I had been sent abroad from England when I was five years old, after the death of my parents, of whom I had no recollection at all, and about whom I knew nothing.

My past memories were all of life as a young boy in Africa, with the man who was my Guardian, and called so by me. He told me that he had been an old friend of my mother’s family, no more, and until his own death, when I was seventeen, he never spoke to me at all about my birth, early upbringing, home or family. Those places and people, those first years of my life, might never have been, and such faint memories as I had of them I must quickly have learned to suppress for my own peace of mind – and so they became quite buried.

Whether I had been happy or unhappy, what I had been before, I also did not know. Only in dreams, sometimes, or those odd, fleeting moments of half-awareness, did I catch a fragment of some mood, some inner sense or feeling or vision – I am uncertain what to call it – which I assumed, because it bore no relation to anything in my present life or the world now about me, must be related to those early years of my life in England.

My Guardian was at that time living in the hills of Northern Kenya, and it is from there that my first conscious memories date. We lived in a roomy, airy bungalow on a farm, and I went to an elementary school in the town twenty miles away. The education I received there was less than adequate, though I think that I enjoyed my days well enough. My Guardian possessed a good, solid, middlebrow library which I had the run of, and it was through this that I made up for many of the gaps in my school learning.

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing