- Home

- Susan Hill

Old Haunts

Old Haunts Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Prologue

Old Haunts

Copyright

About the Book

One hot summer’s day, an old flame turns up at Lafferton HQ and Simon Serrailler is catapulted back to his days as a fresh-faced PC in the Met.

That long febrile summer in the early 1990s, London was reeling from one IRA bomb warning after another. Sirens. Blue lights. Tyres screaming. People running. The army called in. And Simon in the thick of it. Until he’s pulled aside and put on a very different kind of job: his first undercover op awaits. Will the young Simon be able to hold his nerve? Or is he walking into a trap?

About the Author

Susan Hill has been a professional writer for over fifty years. Her books have won awards and prizes including a Whitbread award, the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize and the Somerset Maugham Award, and have been shortlisted for the Booker Prize. She was awarded a CBE in the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Honours. Her novels include Strange Meeting, I’m the King of the Castle, In the Springtime of the Year, A Kind Man and From the Heart. She has also published autobiographical works and collections of short stories as well as the Simon Serrailler series of crime novels. The play of her ghost story The Woman in Black has been running in London’s West End since 1988. She has two adult daughters and lives in North Norfolk.

www.susanhill.org.uk

Old Haunts

A Simon Serrailler Short Story

Susan Hill

Prologue

June and the fourth day in a row of blistering heat. New patches of tarmac on roads and pavements had started to soften and then to bubble, and people living in high-rise blocks of flats were bubbling too, with pent-up tiredness and irritability because they could not sleep, or open any windows to let the stale warm air escape. Extra police patrols were sent out in case some small incident triggered a major one; all the emergency services were alert for young men plunging into Lafferton’s river and canal to cool off – sometimes young men who could not swim.

Simon Serrailler was in his office in the corner of the station building. It had two large windows facing south and west and only one had a blind of which half the slats were broken and it was permanently stuck at the top. His secretary had put in urgent repair requests for months, but Serrailler thought these went, unread, into a black hole purpose-built for all such chits. He had his jacket off, shirtsleeves rolled up, tie off, collar open, and he had a morning of routine paperwork which should have been completed last month. He had not been idle, just exceptionally busy and out of the office, but now several weeks of random assaults on shoppers in the streets had been brought to a conclusion and he no longer had a reason for not looking his computer screen in the eye.

Displacement activity was required and he left his own office and started to cross the floor to where Jenny, his secretary, sat. She looked cool and in control, as usual.

‘If you’re heading for the water cooler, it’s broken. Canteen has run out of chilled bottles of everything.’ She looked up at him briefly and smiled. ‘I could make you some coffee and let it go cold.’

He made a gesture of throwing something at her and went back to his own desk.

Seconds later, the noise of screeching brakes and then the crump of metal on metal came up from the street. He was about to leap up and go to the window but quickly decided others were nearer and none of it had anything to do with him. He was not going to let himself turn someone else’s accident into another displacement activity.

He worked steadily for twenty minutes until Jenny put her head round the door. ‘The lady whose car was driven into – she’s fine, her car isn’t – was on her way to see you. There’s nothing in the diary.’

‘I’m not expecting anyone. Who is it?’

‘A Dr Cartwright.’

‘Doesn’t ring a bell. Can you find out more? I’m up to here. I have to finish this.’

‘Desk says “Dr Nina Cartwright”,’ she said, seconds later.

‘Still no. What ran into her anyway?’

‘Patrol car, thinking he was in a Formula One.’

Simon groaned. ‘Right, well, that’s not for me to sort out. Say no nicely – I haven’t a clue who she is.’

But she was back. ‘She’s apologised and says of course you wouldn’t know her married name … she’s Nina Blake.’

And a chunk of Simon’s past broke off and rose to the surface.

She looked the same and so, he supposed, did he – just twenty years older.

‘Are you OK? Have they had the doc check you over?’

‘I’m fine. I was a bit shaken but a cup of police tea sorted it. The car is a mess but the police insurance will pay for it … Sorry about re-entering your life in such a dramatic way, Simon.’

They went out of the station into the sunshine.

‘I can’t tell you how pleased I am to see you – and not only because you’ve got me out of a load of tedious reports – even if only temporarily. I’ll take you to the Cypriot cafe – it does great coffee. Though half the station may be in there too.’

In fact, no police were there and they sat outside under a parasol with iced coffees.

Nina had never been beautiful but had always drawn people to her, because of her vivacity, her sparkle, her empathy with everyone and everything, from the man sweeping the streets to a stray dog, the senior consultant to the mortuary attendant. She had been in Serrailler’s year when he had gone to med school and there had not been a man who had not fallen for her or anyone at all who had not wanted to be her friend. She was clever and clearly going far, but she had a sympathy which would have served her well all on its own. He had been in love with her, had a brief affair with her, had his heart broken by her, in the kindest, gentlest possible way. She had been one of the people he had agonised to over his struggle about whether to stay in medicine or not, the one who had given him the best advice. He had shared a small flat with his sister Cat, in a sixties block which had seen better days, near to the river, before the area had been gentrified, and everything had gone over a million pounds. Simon had liked it there, being among real people, often the desolate and destitute, criminal and otherwise dodgy, the lonely and the odd. It was half an hour by bike from the hospital and it had been his refuge.

‘How did you find me?’ he asked. ‘And why now, after twenty-plus years? Not that it isn’t good to see you.’

‘I had some notion at the back of my mind that you were in Lafferton – must have read something about your heroics. Anyway, I’m speaking at a conference – at Bevham General. Cardiologists. Nothing starts until this evening so I looked you up and took a chance.’

‘You’re still in London.’

‘Why do you think that?’

‘I’m just assuming … best hospitals and all that.’

‘Actually, no, I’m at Papworth, have been for nearly four years.’

‘Sorry. Not all the best hospitals, of course. So, big cheese then.’

Nina made a face and he made a note to check later. She would have got the top job, won all the prizes, that was certain.

‘And married.’

‘Yes. Ralph Cartwright.’

‘Of course – yes. Now there is a hero.’

Nina smiled. ‘You don’t know the half of it.’

Cartwright was a plastic surgeon who spent chunks of his working life in war zones restoring the faces of children who had been caught by bomb blasts. He left the country and went under the radar, his whereabouts not even known to his family, for weeks at a time. He had been in a bomb attack himself, in Aleppo, but by a miracle escaped with only cuts, bruises and permanent deafness in his left ear.

/> ‘Is he somewhere now?’

‘No, he’s doing facial reconstructs on some burns victims on home ground – until the next time.’

She looked at her empty coffee glass and Simon hastily ordered two refills.

‘It changes him, Simon,’ she said. Her face was troubled. ‘It would change anyone. When he comes back, we have to treat him very carefully, no questions, no pestering him, and certainly no reaction to his moods. He gets irritable, he flies off the handle. The children know to keep out of the way.’

‘How many children?’

‘Two boys – thirteen and eleven. The eleven-year-old has Down’s syndrome.’

Her look switched from troubled to something very different. ‘And it’s fine, we love him, wouldn’t have him any other way, don’t you dare make any remark at all and especially not a pitying one.’

It would not have crossed his mind.

‘I do understand,’ he said. ‘Well – about pity, at least. Cops don’t like pity either, whatever traumatic situations they find themselves in. There is a well-established understanding in the military about the aftermath of terrible experiences but the police still haven’t caught up.’

‘Sounds like you’re talking from experience.’

Simon shrugged. ‘Probably my worst experiences were in my first dozen years in the Met. I was undercover and the times were pretty explosive. Literally. But let’s not go there.’

Nina put her hand on his. ‘You haven’t changed, Simon Serrailler.’

He thought she was probably right.

He drank his second coffee, and did not enlarge upon what he had said. They sat on in the sun, enjoying this time together, catching up on families, remembering other people from their med school days. It was delightful, and when she left, she took his contact details. They might or might not meet again – her conference was three full-on days and then she had to return home. He promised to look her up if he was ever in Cambridge. He kissed her on both cheeks as she left, making sure she had a car to take her to her hotel. The idiot who had driven into her would be hung, drawn and quartered, but not by him.

When he got back to his baking hot office, it was to an urgent message about a stabbing at the Eric Anderson Academy. Uniform were dealing but CID had been called in.

He did not get a chance to return to his computer for the rest of the day, let alone think about either Nina Cartwright or the events which, when he was twenty-four, had left the scars on him.

That came later, the memory unspooling as he sat with the windows of his flat open onto the warm air. The trees in Cathedral Close were still, the grass yellowing in patches. The night smelled of stale heat and petrol fumes.

He did not read his book, or draw, did not watch the television news, did not do anything, for a long time, except go back into the past and linger there.

A long hot summer in the early nineties and one bomb warning after another. Recently, all of them from jokers.

‘They’re no joke though – hoax calls, false alarms,’ Ian Palmer said. ‘Is that the worst of it, do you reckon?’

It was a quarter to one and London could not sleep. They walked through Soho, which never slept anyway. Doorways enclosed small groups, smoking, with beer and cider glasses and wine bottles spread around. Everywhere smelled of heat. Pubs, clubs, cafes were in full swing, with more drinkers outside St Patrick’s Church in the square. But there was no shouting, no fights. Perhaps it was still too hot for that, and with luck, by the time it had cooled down a bit, PCs Serrailler and Palmer would be off duty.

They turned a corner into Chinatown, where it was quieter.

‘They’ll have to stop sooner or later. Give in.’

‘You’d think.’

But the IRA and its bombs seemed to Simon like a problem without a solution. Maybe most wars did. But other wars had come to an end – look at the Cold one.

‘Starry, starry night.’

Ian picked up the tune, whistling softly.

Their walkie-talkies squawked at once.

‘Bomb warning, repeat bomb warning, received 0.38 hours. Report of a bomb planted Piccadilly Circus. Code word Tulip. All officers in W1 area to Piccadilly Circus.’

They could both run very fast.

Sirens. Blue lights. Tyres screaming. People running against them as they headed down Shaftesbury Avenue, wild-eyed.

Palmer was a few paces ahead, and when they got there the Circus was already being cordoned off, army vehicles arriving. Other beat officers came pounding in, heading towards the statue of Eros, the focal point.

‘Bomb disposal,’ Palmer said. Simon looked around. Everything seemed frozen, though there were too many people for this time of night.

Nothing happened and they were moved, ten yards, fifty … ‘Back … everyone back.’

‘Hoax,’ Palmer said. ‘Got to be.’

‘How do you know?’

‘The code word. Tulip!’

‘Why not tulip?’

‘Because it’s meaningless in the context – when it’s genuine, the code word always gives the clue. Michael Collins. Falls. Troubles. Tulip’s like that last one – “Toffee”.’

The bomb disposal guys were in now and had Eros and the area around it to themselves. Or rather, ‘guy’. Just the one. The others were backup.

‘Starry, starry night.’

The all-clear was given at twenty past two.

‘I could string ’em up. Bloody hoaxers,’ the desk sergeant was saying to anyone who came through the station doors.

‘Better than the ones who do it for real.’

‘Tulip!’ Palmer snorted.

A day later there was a briefing on the recent hoaxes, as well as a going-over of the last actual terrorist bombing, two years previously. Simon had been a medical student when that bomb had gone off, his hospital the nearest to the site, and he remembered that what had seemed like chaos had rapidly formed itself into a well-rehearsed and orchestrated response. All lectures had been cancelled and students had been ordered away from the A&E area, but he had gone as near as he dared and the porters had been glad of help. At the time, he thought he would never see worse traumas.

Now, a whole new intake of constables since that incident plus a few transferred CID were in the room. Gold Command from that night was talking, a retired bomb disposal expert and an incident coordinator were lined up ready.

The first hour filled them in on the motives and credo of the IRA and of splinter groups, though there were too many, and little was known about a lot of them, to go into detail. The history was a sprint-through with references on the whiteboard for them to read in their own time.

‘Right – this is an imaginary incident and we’re going through it minute by minute, from the moment the warning call comes in. A mock-up, in real time, starting when the hands on that wall clock are pointing to 11 a.m. Steve will take the other side, which means we’ll be privy to what their plans and actions are, though naturally that would not normally be the case, unless we have a mole – and how often do we? Generally, we’re working blindfold in the dark, and as events unfold – and they unfold with lightning speed, let me tell you. Is this going to be a real bomb warning or is it a hoax? Are we going to have to put Operation Caterpillar into action fast or stand everyone down? It’s like one of those war games you played on a board when you were ten years old and the little plastic battleships were lined up. Difference is, those battles were never going to happen. This has and it could again. Listen up.’

The next hour sped by as they caught up in the moves on the board, the variables, the possible outcomes.

They were given roles, they were put into teams, then isolated. Another half-hour and they had successfully identified two hoax warnings and missed a genuine one. At the end, they had made the right call on the fourth and then almost messed up the response.

‘Roughly four hundred people were nearly blown up, an entire block of our police area came within an ace of being obliterated, and many of

you almost ended up in hospital, missing limbs or bits of whatever brains you are supposed to have started with. It isn’t a game, you see. Any of you in doubt about that? Right, I want you to remember everything you’ve learned in here – and that means everything. Digest it, go over and over it, turn it upside down and inside out and subject it to rigorous questioning. You can go.’

Simon was halfway down the last flight of stairs when the man behind tapped him on the shoulder. ‘Sarge wants you.’

‘I’m not on duty.’

‘Don’t shoot the messenger.’

The front desk was knee-deep but, seeing Simon, the sergeant handed him a note on which was scribbled ‘Room 19, top floor’.

He had no idea what it was about and was mildly irritated at another interruption to his free day, but he calmed down, standing to one side of the mayhem of arrested bodies being brought in, people demanding to see this or that cop immediately, drunk people, people coming down from highs, people wanting to report missing cats … with all of whom the desk sergeant dealt slowly, patiently and in some sort of order.

Room 19 was a small, rarely used interview room at the end of a corridor. Serrailler hesitated. Listened. Silence.

He knocked.

The two men were in plain clothes. One was older, with a grizzled very short haircut; the other was anonymous-looking, possibly in his thirties, possibly a bit younger. Brown hair. Brown eyes. Medium height. Pleasant, unmemorable features. A man who would not stand out in a crowd, would blend into any group. You could look carefully at all of him or just his face but not recognise him in the street later. He wore a grey T-shirt, jeans, grey trainers – grey from wear and scruffiness.

‘Please sit down, PC Serrailler.’ The older one. They had taken seats close to the wall and away from the door and windows. As he joined them, the younger one got up and went across to the door, looked out both ways, then closed it and came back.

The older man looked at Simon. ‘I’m John. This is Nick. Ranks not really relevant – our unit isn’t very hierarchical – but for the record, it’s Super and DCI.’

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

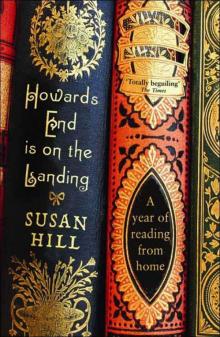

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

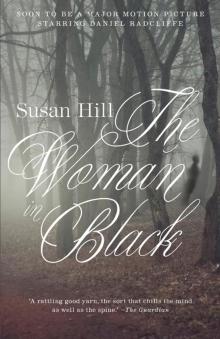

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing