- Home

- Susan Hill

From the Heart Page 10

From the Heart Read online

Page 10

And after all, the hotel proved a good idea. It was festive, fun, cheerful and good to watch others. ‘People spying’ Peggy called it. In the flat, they would have made false conversation. Here, it seemed easy, in the noise of the dining room, with families and children as well as couples. The food, what she could eat of it, was good but her appetite was still poor.

And all the time, all the time, she was in a frenzy of uncertainty and emotion. She tried to push the thoughts away, to switch them off as they ran like moving messages through her head, tried to replace the images with others from other times of her life. But she could not. In the end, the feelings drove her to say, early on Boxing Day morning, that she wanted to walk by the sea a little, on her own.

‘There is so much to think about and plan for the start of term. Besides, it will give you some time together.’

So far as she knew they spent most of every day and every night with just one another. If they had made new friends, none were ever mentioned.

It was cold and clear, the sea like bottle glass and she did as she had been bidden and took deep lungfuls of air. People walked smartly, believing that it was doing them good. She could not and several times she leaned on the railings to look at the sea, but not seeing it, seeing always, Thea.

She had never been in love, nor, so far as she knew, had anyone loved her – certainly not Malcolm, though he had liked her, perhaps been fond of her. If they had married, perhaps they might have been happy enough. Who knew? Perhaps it had been his parents who had wanted it, pushed him to ask her. Perhaps he had tried to defy them. If so, she would have respected him for it.

No. She walked on. Not ‘enough’. People should not marry to be ‘happy enough’. Because she had never fallen in love she had never been sure what to expect, only that she would recognise that it had happened when the time came. So, was it this? This overwhelming desire to see someone, be with them, and to tell them everything, all the truth that had ever been told. Was it talking to them in your head, as she did now, as if they were never not there? She traced Thea’s features, eyes, nose, mouth, her hair, her hands, in her mind.

Yet she had run away. Whatever this was, it filled her with fear and embarrassment and the strange sense of being doomed. It was not usual. It was frowned upon. It disturbed her profoundly. She thought that she ought not to go back, but give in her notice, on the grounds of ill health, and loss of nerve for teaching. She could return to the flat to pack up. It would take her only a couple of days and she would not step outside the door or see anyone at all.

Why should she do this? What was she afraid of?

She sat on a bench and turned her coat collar up against the wind.

Of what people might say. Would say. What they would think. How they would judge her.

But how much would those things matter?

Of taking the wrong road, then, and missing the right one.

Of following her feelings, which might turn out to be like a house built upon the sand.

Of ruining her career, her promising career, when it had barely begun. It was the right career, that was the one thing of which she was certain.

Of Thea.

Yes.

No.

Not of Thea herself, but of the power of Thea’s own feelings, which might sway her against her rational judgement, and take her in the wrong direction.

What was that? What was the right direction?

She got up and walked on as quickly as she could, because she was cold and because her head was bursting.

There was no one at all she could talk to, except perhaps Margaret, who had never given pat replies or put the conventional view. She thought things through. She gave her own opinion.

She could not travel up to York. But she could write.

That evening, she made half a dozen attempts at starting a letter but always stopped when she reached the point of telling. Confessing? Asking. Every phrase she wrote sounded either clinical or evasive and when she read them on the page, read her own handwriting, she felt exposed and awkward.

Ashamed?

But in the end, she chose what seemed the least embarrassing, more matter-of-fact phrases, and sent the letter.

She went back to the flat after another couple of days. The time with her father and Peggy had been easier than she had expected, she had felt more at home, less tense, though she had still tired easily.

Had they enjoyed having her to stay? They were polite, they told her to go back as often as she liked, but she sensed that they were happy in the small world of their apartment, happy and close. Perhaps more than her father and Evelyn had ever been.

It was unnerving to be back home. She had only a swirling fog of memories of being ill there and she felt like a stranger in the rooms, which seemed dark after the seafront flat. Little seemed familiar and what did reminded her of a long-past life. The sense of dislocation would lessen, she knew, and that she would be perfectly well enough to return to school the following week.

Except for Thea.

Thea had not ceased to occupy every corner of her mind and every waking minute and to fill her dreams.

Thea.

She went over and over the wording of her resignation letter. It must be simple and clear – and definite. There was the question of a reference. She intended to go to a school in some distant part of the country, she had no idea yet where, but there would be advertisements to which she would respond. Could she ask for a reference after such a short time at Barr’s? Her illness was not her fault and would surely not be held against her, but there must be other good and credible reasons why she should leave. Perhaps she did not really care. She thought only of Thea and Thea was not a reason to which she could ever admit.

She switched on the lamps. There was a small pile of books beside the chair. Peggy had sent her back with a package of food, eggs, cold meat, some leftover cheeses and a slab of the Christmas cake.

She would eat, and then write the letter.

Eat the eggs. Eat some cake. Write the letter.

Make a cup of tea and write the letter.

Settle down and then write the …

The doorbell rang once, as if someone had pressed it gently.

There was a flicker of a moment in which Olive knew that she had to choose and that once the choice was made she would never have it or any power over its consequences again. The flicker of a moment was out of time, as such moments generally are. It lasted an hour or a day or a lifetime or the fragment of a second. She had endless time in which to decide, all the time that was or had been or would be for the rest of her life. She had a flicker of time in which to be born and grow and live and die, in which to choose whether to leave and never once look back or acknowledge that this had been.

She had a flicker of time in which to refuse.

To accept.

Yes.

Afterwards, it seemed to her that she had never had a choice but had been quite powerless all along, but that was not true, she simply forgot.

She lit the fire and they sat together beside it and when Thea touched her, reaching over and taking her hand, Olive understood at once that she had never been touched before or never felt herself respond before.

‘How did you know I was back?’

‘I didn’t …’ Thea stroked her hair. ‘I came past every day, to see if there was a light.’

They talked then, of each other, of their pasts, hopes, dreads. Of love, but not yet of lovers.

‘What will we do?’ Olive sat up, the reality of it making her heart race. ‘What will happen?’

Thea was silent for a moment and when Olive looked at her she saw both thoughtfulness and also anxiety, on the face she now loved.

‘Nothing will happen. We found one another.’

‘Yes, but there can’t be any future for us.’

‘Of course there can! What are you afraid of – what people might think? Or say? But people needn’t know.’

‘No, but they will find out.’

‘No, because we won’t tell them or make it obvious.’

‘All the same … won’t it be best if I just leave the school? I was going to resign anyway.’

‘Why?’ Thea drew back from her.

‘Because of this … You. I didn’t even know if you … I didn’t know anything, Thea. I couldn’t bear to be with you every day if I had just made some stupid mistake … fantasy … I don’t know. It just seemed best to resign.’

‘I love you. There. Will you leave now?’

‘Leave you?’

‘The school.’

‘Yes. It’s even more important now, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t know … and that is the truth. But – perhaps.’

‘There are plenty of schools.’

‘None as good, not for a long way, and you don’t want to take any old teaching job, you’re too good.’

‘I’ll get another sort of job.’

‘No, you won’t. You won’t do anything. Not yet. Not in a rush.’

‘Where will you be?’

‘Be?’

‘Live. I want to live with you.’

‘I don’t think so, darling. That would be too obvious. We have to be aware of other people, even if we disagree with them – of what they think, what they say.’

‘So I will stay in the flat?’

‘Yes. Please don’t worry. And don’t be afraid of anyone or anything.’

‘No.’

No.

When Thea left at one o’clock that morning, slipping quietly down the stairs and out into the silent lane, Olive lay in her bed, awake and awake, feeling herself to be wholly new-born and barely known.

She returned to school and the first department meeting of the term and sat on the far side of the table, to Thea’s left, so that it would be impossible to catch her eye.

‘My dear Olive, how very good to have you back! Are you quite better? You’re very thin.’

Sylvia patted her shoulder, her face creased with smiles and goodwill, sat next to her and went on smiling, as she smiled encouragingly to girls who blushed and stammered when asked to read aloud. A good woman, Olive thought, looking at Sylvia’s jade-green beads which had one in the string missing, and the buttons on her blouse whose top two buttons were done up the wrong way. She remembered that they had laughed at Miss Barlow, who always had something wrong with her clothing, and pins falling out of her hair. And she had been a good, kind woman too and they had never seen it, too busy as they always were to snigger at her getting awkwardly onto her bicycle and sailing off down the road, with her hair gradually coming undone.

What would Sylvia say, if she knew? Would she be shocked into silent disapproval, or be generous and understanding?

Thea was talking about the A-level syllabus – too many Victorians, too much that was tired and obvious. ‘The Old Faithfuls.’ Olive agreed but said nothing and did not even glance up.

‘And one more thing – we need to wake up lower four B. They’re like rows of suet puddings. Has anyone else managed to get a spark out of them? No, I thought not. Isn’t it odd how it goes like this … one class is sparkling with eagerness and enthusiasm and another is like the walking dead. If anyone can suggest a book that will set them alight?’

‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde,’ Olive said, without having meant to say anything at all.

Thea looked round at her and away again. ‘That’s an idea – it isn’t long but there’s plenty of meat on it … lots to discuss.’

‘Well suggested!’ Sylvia said. The little pat on her arm again. Olive felt her face heat.

They moved on to talk about the production of The Crucible.

26

THEA CAME TO the flat every other day and on Sundays they drove out to walk over the Downs, sometimes in bitter winds, but where they saw no one they knew and they felt free and untroubled. They found pubs in which to drink whisky and warm themselves, before returning to Thea’s car, and Olive felt that the strangers they came upon must see at once that she was lit up by love, that it was visible, forming around her like phosphorescence, and when she looked into Thea’s eyes she saw that they reflected the same joy.

‘Why am I not allowed to see where you live?’ she asked suddenly, as they sat watching the rain sluice down the car windows. Veils of it hid the hills.

‘Of course you’re allowed! Listen, I am only trying to spare you. I have never said anything because – well, actually, I suppose there is no good reason. But my mother lives with me and she is confused now, and anyone she doesn’t know worries her. She can’t cope with any sort of novelty, or disturbance … she’s fine when she’s among familiar things and with people she knows. That’s all.’

‘But … I’m sorry. I wasn’t prying.’

‘There’s no such thing – not between us. How could there be? Of course I should have told you … it was stupid and you must have thought it very odd.’

‘In a way. It doesn’t matter now I know.’

‘I wasn’t trying to shut you out.’

‘No, and I understand. Of course I do … Is she alone all the time when you’re at school?’

‘Not all the time … we have good neighbours and someone goes in every day to get her lunch and generally keep her company. She’s in her late seventies but her mind is – no age. A child’s age again. It’s easing off – come on, make a run for it.’

There was only an electric fire in this particular pub but there were good ham sandwiches, and a table in the dimly lit corner.

‘I am happy,’ Olive said, closing her eyes with the impact of it, ‘I am so happy.’

Thea took her hand. ‘I wasn’t trying to keep secrets.’

‘Of course not … and some things are not necessarily for telling.’

‘I want to tell you everything I can.’

Everything. Olive looked into the glowing red coils of the fire. Everything.

What had she told? Childhood. Her mother. Father. Her mother’s death. Peggy. College. Malcolm. Dr Faustus. Penny. James.

She felt her hand curled in Thea’s. She felt her own happiness.

She felt safe. A new life.

Safe.

She still did not fully understand it all but she no longer felt like running away, or that she should deny it.

She and Thea. Whatever it was, they were. But she had told her the bare facts about James. She had told her about meeting Malcolm. Going out with Malcolm. Staying with his family. And she made light of it all.

Beyond the bare facts, there was a door and it was locked and bolted. James was on the other side. Safe. No one else went there.

James, pink mouth, puckered like a sea anemone round her breast. She all but felt the force of it as the mouth sucked and pulled and there was an answering pull inside her, as well as in her breasts, a tug which was very strong but quite painless.

‘What is it?’

She surfaced. Breathed. ‘Nothing.’

Thea lifted Olive’s hand to her mouth and bit the little finger very gently and there was the same responding tug inside her. Strong. Painless.

They left and ran again through the rain.

And the weeks and months went by in the same haze of joy and disbelief, without any pause for concern or even to think, though the time was punctuated by days when work took first place, and then they simply set their own lives aside safely and gave their whole attention to pupils, lessons, preparation, books, marking, meetings and The Crucible.

Thea was directing it and there were two and then three after-school rehearsals a week until Easter. When they came back at the end of April, there would be more.

‘The school play,’ Thea said, ‘takes over.’

‘What can I do? I could be on the prompt book. I’m quite good at it.’

‘Ah – Dr Faustus! I’m sure you are but Sylvia has been on the book for every school play since time began. She would not give it up unless it was prised from her hands – and even then.’

Meanwhile, she

had a week when her mother went to stay in a home, she said, always the same one, which she knew and liked.

‘A week. Where shall we go?’

Suffolk was milky skies and seal-coloured, gull-coloured shingle and the first curlews mournful across the marshes. They rented rooms overlooking the sea and watched the fishing boats riding in on the waves and lay together hearing the crash and boom of them as the tide came up the beach. Walked. Sat on the sea wall. Talked. Talked.

‘Have you always known?’

Thea usually turned her head to look at her when she replied but now she continued to look at the silver line of the horizon.

‘No. Well – perhaps. But hidden so deep I could never have dived down to it. And I was married.’

Olive had no idea what to say.

‘For six years. He – Philip – taught Classics. We started as trainees in the same school.’

‘Did … no, it doesn’t matter.’

‘Ask anything – I don’t mind.’

‘No. It’s not for me to know.’

‘I want to tell you everything. And know everything. That’s how it is.’

‘Yes.’

‘There isn’t much anyway. We were perfectly happy – we got on well, we shared interests, we liked one another’s company – that counts for a lot, you know. I suppose we loved one another. Yes, of course we did. But we were never in love in the way that we should have been. We didn’t know that, of course.’

‘What happened?’

‘I met someone else. And as chance would have it, so did he – at the same time. We parted quite amicably. He died of leukaemia, a couple of years ago.’

Something in her voice indicated that despite her saying she wanted to tell Olive everything, that door had closed. No more would be told her, and she was warned not to ask.

Thea took her hand. ‘You might as easily have married Malcolm.’

‘I would never have done that.’

‘Because you didn’t love him?’

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

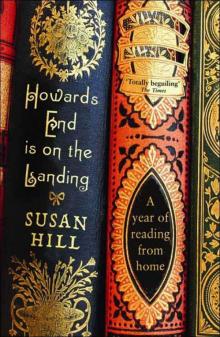

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing