- Home

- Susan Hill

A Question of Identity Page 3

A Question of Identity Read online

Page 3

Page 3

Charlie Vogt held the door open to let in a woman he knew from CID. She nodded to the defendant who had just come back into the dock and made a face. Alan Frederick Keyes. Not bad-looking. Charlie wanted to ask her for a woman’s opinion but there was no chance, she’d gone along the benches. Besides, was it relevant? He had the blood of three elderly women victims on his hands. What else mattered except that he’d be leaving that dock and going down for life? Charlie felt a spurt of bile come into his mouth. Once in a while, anger and loathing turned your stomach.

The door bumped to immediately behind him, deadening the murmur from outside, where the news that the jury was back had filtered out. The TV cameras were getting ready, furry mikes swaying on their extension rods. Beyond them, the crowd had filled out, the news having travelled like magic to those who had just been waiting to hear and then shout, punch the air, call Keyes every filthy name they knew. The murders of little children and old ladies – it brought the mass hatred out and roaring like nothing else.

In the street beyond, cars slowed, even a bus, faces peered out before the lights went green again. Police stood about, arms folded, watching, waiting to hold back the rush when the prison van emerged later, Alan Keyes in the back, cowering as fists thudded on the metal sides.

I read about this Russian. He was fine but then when there was a full moon – or maybe it was a new moon? – no, a full moon, definitely – when that came, he went mad inside, he had to do it, that was when his head was bursting.

THE COURT WAS full to overflowing, the public benches packed. Charlie and Rod stood pressed against the doors poised like greyhounds in the slips.

You never got over it, Charlie thought, your blood pressure went up with the tension and the excitement. Better than any film, better than any book. There was just nothing to beat it, watching the drama of the court, eyes on the face of the accused when the word rang out. Guilty. The look of the relatives, as they flushed with joy, relief, exhaustion. And then the tears. These were the final moments when he knew why he was in his job. Every time.

Alan Keyes stood, face pale, eyes down, his police minder impassive.

Charlie’s throat constricted suddenly as he looked at him, looked at his hands on the rail. Normal hands. Nothing ugly, nothing out of the ordinary. Not a strangler’s hands, whatever they were supposed to look like. But the hands, resting on the rail, hands like his own, one beside the other resting on the rail, resting on the . . . those hands had . . . Charlie did not think of himself as hard-boiled but you did get accustomed. But nothing prepared you for the first time you saw the man in front of you, ordinary, innocent until proved guilty, however clear his guilt was, nothing prepared you for the sight of a man like Keyes, there in the flesh, a man who had strangled three elderly women. Nothing. He couldn’t actually look at Keyes at all now.

The lawyers sat together, shuffling papers, fiddling with box lids, not looking at one another, not murmuring. Just waiting.

And then the door opened and they were filing back, concentrating on taking their seats, faces showing the strain, or else blank and showing nothing at all. Seven women, five men. Charlie was struck by the expression on the face of the first woman, young with dark hair pulled tightly back, bright red scarf round her neck. She looked desperate – desperate to get out? Desperate because she was afraid? Desperate not to catch the eye of the man in the dock, the ordinary-looking man with the unremarkable hands who had strangled three old women? Charlie watched as she sat down and stared straight ahead of her, glazed, tired. What had she done to deserve the past nine days, hearing appalling things, looking at terrible images? Been a citizen. Nothing else. He had often wondered how people like her coped when it had all been forgotten, but the images and the accounts wouldn’t leave their heads. Once you knew something you couldn’t un-know it. His Dad had tried to un-know what he’d learned about Hindley and Brady for years afterwards.

‘All rise. ’

The court murmured; the murmur faded. Everything went still. Every eye focused on the jury benches.

In the centre of the public benches a knot of elderly women sat together. Two had their hands on one another’s arms. Even across the room, Charlie Vogt could see a pulse jumping in the neck of one, the pallor of her neighbour. Behind them, two middle-aged couples, one with a young woman. He knew relatives when he saw them, very quiet, very still, desperate for this to be over, to see justice being done. Hang in there, he willed them, a few minutes and then you walk away, to try and put your lives back together.

Schoolteacher, he thought, as the foreman of the jury stood. Bit young, no more than early thirties. Several of them looked even younger. When he’d done jury service himself, several years ago now, there had only been two women and the men had all been late-middle-aged.

‘Have you reached a verdict on all three counts?’

‘Yes. ’

‘On the first count, do you find the accused guilty or not guilty?’ The first murder, of Carrie Gage.

Charlie realised that he was clenching his hand, digging his nails into the palm.

‘Not guilty. ’

The intake of breath was like a sigh round the room.

‘Is this a unanimous verdict?’

‘Yes. ’

‘On the second count of murder, do you find the accused guilty or not guilty?’ Sarah Pearce.

‘Not guilty. ’

The murmur was faint, like a tide coming in. Charlie glanced at the faces of the legal teams. Impassive except for the junior barrister of the defence who had put her hand briefly to her mouth.

‘Is this verdict unanimous?’

‘Yes. ’

‘On the third count, do you find the accused guilty or not guilty?’

His Honour Judge Palmer was sitting very straight, hands out of sight, expression unreadable.

‘Not guilty. ’

‘Is –’

The gavel came down hard on the bench and the judge’s voice roared out: ‘Order. There must be silence for the clerk to finish his question to the foreman of the jury and for him to reply. If there is not I will clear this court immediately. ’ Judge Palmer’s eye glittered. ‘These are the gravest moments of the entire trial and the court must remain silent. Will the clerk now please ask his final question and the foreman give his reply?’

‘Is this verdict unanimous?’

The foreman had been composed. Now, briefly, he looked terrified. ‘Yes. ’

The court erupted.

Charlie caught Rod Hawkins’s eye as they both made for the doors through the crowd, trying to beat the rest of the press pack to it. By the time they were outside, the news was ahead of them, the corridors and front lobby of the building seething with people relaying the verdict. The few police on duty outside were calling for backup and getting into position to restrain the crowd and prevent them surging into the front area.

Charlie Vogt stood on the steps listening to the sound of anger that was growing, becoming a roar, like a tide racing in towards the court building.

Rod was beside him. ‘What the f*ck . . . That lot are baying for blood. What’s going on in there?’

Without consulting one another, they headed back down the corridor, weaving and dodging through the crowd coming out, others standing about the hall in stunned groups, briefs charging past, gowns flying.

By the time they reached the doors of Court Number 1 the mass of people had left, driven out by the officials. Alan Keyes stood in the centre of a knot of police and clerks, his defence counsel and the rest of the team behind.

‘You can’t stop me,’ Keyes was shouting, his eyes swerving round the group, to the clerk, to the uniforms, to anyone who could hear him. ‘I’m a free man, didn’t you bloody hear? Not guilty, not guilty, not guilty. He said so. ’ He pointed to the empty jury benches, then round to the judge’s chair. ‘Not guilty. I’m a free man and I’m going out there to tell them s

o, I’m walking out those gates, I’m discharged, and you can’t hold me in here. ’

The police stood conferring. The barristers looked troubled.

Charlie and Rod stood by the doorway, their presence not noticed in the scrum.

‘He’s right,’ Charlie said.

‘If he goes out through those doors he’ll get torn apart. ’

‘Get the f*ck out of my way, clod. ’ Keyes lurched forward and took a swing at the copper. The blow made no contact, but within seconds Keyes’s hands were behind his back and cuffed. In the middle of yells and curses of protest, he was cautioned by one officer and restrained by two others.

‘Gotcha,’ Rod said. ‘Though they can’t hold him for a fist that didn’t connect. ’

But Charlie Vogt was already sprinting for the doors.

She had sandals on with a mended strap which came apart as she ran so that she tripped and almost fell on her face, but didn’t quite, recovered, ran on. She had never moved so fast; she felt like a rugby player dodging this one coming towards her, then that one, then a knot of them together. She ducked and dived, banged her arm against the corridor wall, dodged again, almost pushing over a man carrying a pile of boxes, hearing them crash to the floor as she went on, through a pair of swing doors, down a long corridor where there were fewer people, right to the end, down a short flight of steps. Then there was only the sound of her own running footsteps, the broken sandal slapping unevenly on the tiled floor. She had no idea where she was going but somehow she’d get out, even if it was much later, when they’d all gone. When he’d gone. She’d find an empty room and stay there until the place went quiet, people had all left for home, then try. Nobody would notice her.

Two doors. It reminded her of a corridor at school with classrooms on either side. Both were locked. She stopped to get her breath. From a window high up in the wall, she could hear a muffled sound, like the sea murmuring. A siren, then another came wailing towards the building.

The corridor smelled of chemical cleaner, making her sneeze, and the sneeze seemed to crash around the walls and down the corridor, echoing and re-echoing. She froze, pressing herself against the wall. Nobody came. It was quiet again.

Then, a corner and another door and when she pushed against it, it swung open. She almost fell inside with relief and leaned on the other side, catching her breath in gulps, shaking. And all she could think of was his face when the words were said.

Not guilty.

And again.

Not guilty.

Not guilty.

As they were spoken, and a second before the whole courtroom exploded, he had half turned his head and looked straight at her and the expression on his face, in his eyes, had frozen her to ice.

Now, the ice was thawing and melting, water ran through her body, and she felt herself sliding slowly down until she was a pool on the floor.

You feel as if the top of your head will blow off. Two minutes after you’ve done it you can do anything. You’re, like, the most powerful person in the universe. You’re God.

‘YOU CAN’T KEEP me here. I’m a free man, you heard, “not guilty”. So I should be walking out there not in here with you. And I want my brief. ’

‘Listen –’

‘No, you listen, dickhead –’

‘You can have what you want, Keyes – tea, coffee, something to eat – you can’t have your brief because he’s gone home, and you don’t need your brief because you’re not charged with anything. ’

‘You cuffed me, you dragged me down here, I’m not guilty, you heard. ’

‘Yes,’ the DI said, ‘I heard. ’ He didn’t keep the contempt out of his voice. ‘You attacked a police officer –’

‘I missed. Didn’t get near him. You saw. ’

‘Right. ’

They were in a small holding room in the basement of the court building. It had a metal table and two chairs. Alan Keyes sat in one, the DI in the other. A uniformed constable stood outside the door.

Alan Keyes stood up and pushed the chair over as the door opened and two more men came in.

‘DCS Granger. Sit down, Keyes –’

‘Mr Keyes to you. ’

‘Sit down,’ the Superintendent said, not looking at Keyes.

The other man, who was tall and upright and had a thin moustache, stood beside him. Said nothing. Did not give his name.

‘Now listen –’

‘I want to walk out of this fu**ing building, I have every right to walk out of –’

‘I said listen. There is no way I can let you walk out. No way. Why do you think you were cuffed and brought down here?’

‘I didn’t bloody touch him, I missed, I only swung at him, it wasn’t –’

‘It had nothing to do with you taking a swing at a police officer – we cuffed you and brought you down here and are keeping you in custody for your own safety. ’

‘Piss off. ’

‘Because if we’d let you strut out of that court you probably wouldn’t have made it a dozen yards down the corridor, you would have been set upon, battered to death – my guess is you would have lasted three minutes. You’ve got no idea, have you? There’s several hundred angry people out there, and there’d be more arriving if we hadn’t closed the road. You know why, Mr Keyes? That’s right, you can look terrified. ’

Keyes twisted his expression back into defiance.

‘I’d be terrified if I was in your shoes. You still want to walk out there? You’re not under arrest, as you say, and I’ve no power to stop you, but it’s my duty to advise you that you should remain under police protection. ’

‘You’ll get rid of them, won’t you? Clear the street. Tear gas, water cannon, they’ll bugger off. ’ Keyes smiled. ‘I’m an innocent man. ’

‘Yes, Mr Keyes. Which won’t prevent the public forming its own judgement and acting accordingly. So I’m advising you to accept police protection . . . ’

‘What’s that mean? You put me up in a nice hotel?’

‘We do not. ’

‘I’m not going back inside that fu–’

‘Nor in prison custody. You’ll be taken to a place of safety and then we’ll discuss the choices you might have. ’

‘What choices? I’m going back home, aren’t I? You can’t stop me, a man’s home is his castle, a man’s –’

‘Shut up, Keyes. ’

‘What is this place of safety then? How long do I have to stay?’

‘As I said, you’re not under arrest. We are giving you advice for your own protection. You’re free to take it. Or not. I can’t tell you where you’d go but you would stay until such time as we decide you would be safe to leave. Or make other arrangements. ’

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

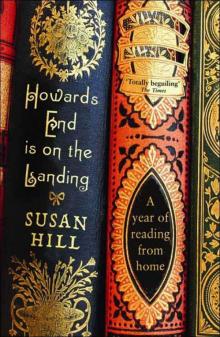

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing