- Home

- Susan Hill

Old Haunts Page 3

Old Haunts Read online

Page 3

‘I nodded off for ten minutes.’

‘Right.’

‘No one’s in next door … or they weren’t earlier. Pretty sure I’d have heard them.’

‘Walls are quite solid actually. Not like the modern cardboard variant. I’m Will.’

‘Right.’

Will. He had a packet in his hand as well as the key. ‘This has three devices – one for the living room, one for the kitchen, one for the bedroom. Size of a drawing-pin head.’

‘Why am I being bugged? Assuming that’s what they are.’

‘You’re not, they are.’ He nodded towards the wall.

‘You’ve got a key to their door as well?’

‘Breaking in makes such a lot of mess, we find.’

‘So you put them in and then what? I listen from here?’

‘It will take me six minutes.’

‘I wait?’

‘Yeah, outside. Wait. Watch. Listen. Warn.’ He took a pager, similar but smaller, out of his jeans pocket and handed it over.

‘I’ve got the other end. Anything at all you press here. Once for a warning – that’s footsteps coming up these stairs, lift stopping on this floor. Twice – get out now.’

‘Coming, ready or not,’ Serrailler said.

Will looked at him. ‘It’s not a bloody kids’ game. They didn’t tell you that?’

He felt the put-down more than he should have done.

‘When are you fitting them?’

‘Now. No time’s a good time if they come back.’

‘“They” being?’

‘The two guys living next door and maybe a visitor.’

‘Is that it? I understand –’

‘No you don’t. OK, go downstairs, stand by the main entrance. Two men coming in together – one ginger, one dark-haired guy who usually wears a red cotton scarf round his neck, both around five foot ten, eleven. You buzz me the second you see them. Anybody else, don’t bother.’

‘I’m just hanging about?’

‘No, you’re cleaning windows.’

‘What …’

‘Of course you’re just hanging about. Main thing is, I get out in time … before time.’

‘How?’

‘Out the door, down the stairs. They’ll use the lift.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I don’t. Just guessing they’re idle buggers.’

Will wore a denim jacket with several pockets, presumably the stash for his tools though, if so, they were not evident. He nodded to Simon and slipped out into the corridor, stood listening intently, then edged his way to the next door, keeping close to the wall.

Simon went fast down the corridor and took the stairs two at a time, his trainers making almost no sound.

He opened the door back into the world of revving motorbikes, emergency sirens, planes coming in slowly, heavily, over London, car horns, the non-stop grind of traffic.

A mild day, a sunny day. Safe.

Nobody was ever safe. It occurred to him that he was being kept in the dark to an unfair extent. No one had been clear about what he could expect to happen to him, no one had given him information about the men in the next-door flat. He had a general description, by which he ought to recognise them, and a vague suggestion had been made that they were part of an IRA splinter group planning violence of some kind in London. So – ‘need to know’?

He caught himself out. He was being resentful – sulking in other words – when he ought to be delighted at having been singled out, a uniform copper for such a short time and now on an undercover op. A big deal. And the adrenaline was pumping through him as he stood there, looking out, even though he guessed nothing was actually likely to happen, or not right now.

A motorbike screamed down the side road, splitting his eardrums and distracting him as two men came round the corner ‘one ginger, one dark-haired guy who usually wears a red cotton scarf round his neck’. Both looked not much short of six foot, which did not trouble Serrailler, at six three.

They took their time, but at a certain point, as if they had noticed him at the same moment, they looked directly at him.

He pressed the button which should have vibrated slightly in his hand. It did not. He pressed again, twice. Nothing. Battery fault? Bugger.

The two men walked on towards him. It was possible that Will had actually got the message, but he could not rely on it and he still had to give him time to get out of the flat.

He made a vague gesture at the men, and started to move away from the door, stumbled and stopped. When they were within earshot, he called out, slurring his speech, ‘Hey. You going inside? Great stuff. Lost key. Hello! Pleased to meet you.’

They stared at him. Glanced at one another, then came slowly nearer. Simon swayed forwards, holding out his hand. The ginger one tried to edge round him but Simon clapped him clumsily on the shoulder. ‘Got a match? Course you have. Come on, come on.’ He held on to him with one hand and tried to access his jacket pocket with the other. ‘Need a match. Buy you a drink. I know you’ve got a match. Give us a minute, then we’ll go over there.’ He waved his hand vaguely. ‘Good pub over there.’

He stumbled again and half fell against Ginger. The pain he felt in his left arm and shoulder for the next couple of seconds almost made him black out, but it stopped as he squirmed away and would have grabbed the man by the collar except that his feet shot from under him, kicked by the second one. He recovered his balance, and as he launched out with his fist, saw Will, out of the corner of his eye, racing away from the block and gone. Relief gave him his fighting strength back in full.

He had thought men like these two only made warning phone calls, recced targets for weeks, planted bombs and drove away, but they had clearly been trained in hand-to-hand and he knew that they, two against one, would get the better of him. If he had no hope of overpowering them, he had only one choice, unless he wanted to be either beaten up or – worse – taken prisoner. A quick strategy formed itself in his mind, in a freeze-frame. He hesitated, so that they did not know what he would do next, and then headbutted the dark one, punching hard and winding him. He buckled. Ginger did not know which way to turn in the next split second, which was all it took Simon to sprint fast, out of sight round the corner of the flats. He dodged left, past the bin area, and then quickly right, towards Victoria House. A woman was coming out; he pushed past her into the lobby, and out of the doors at the back.

From there it was a five-and-a-half-mile walk home. He jogged for the first mile, but the streets were too crowded and he got sick of dodging people on the pavement. One or two indicated that they were sick of him, after he had almost crashed into them.

Walking was fine except that his mind could wander too freely, back to the fight, going over it all, the ginger one lunging at him, the other grabbing him and holding on hard, the sight of Will exiting the flats and running away. Will’s had been the getaway that mattered.

The two men would recognise him, though he thought it was just possible they might already know that he was there and what he was doing. Had they attacked him because of that, or simply because he had seemed like a random loose cannon, a drunk getting in their way? They would be in Flat 24 now, in the next stages of their plan, whatever that was, whenever it was going to happen. That was what the bugs would reveal, if Will had not been forced to abort the job and the plants were working. Had he got the warning or had the buzzer really failed, and if it had, why did he run?

Too many unknowns. But he was pretty sure that he’d messed up, all the same. The idea had hardly been for him to pick a fight, but he was in one piece, he hadn’t opened his mouth. He needed strong coffee and if he was lucky, an hour’s kip. After that? He fished out the pager but there was no message.

If the two men were part of the group which was planning another bomb attack somewhere in London, and Will had got the bugs in place, presumably it could be prevented. If not … Simon had a flash of wondering how he would be able to live with himself, befo

re he put the lid down on the thought.

He walked on, with bursts of running or jogging when the way was clear. He had slipped the key in the back pocket of his jeans as he left and reached for it as he went up the stairs, but when he tried to turn it in the lock, it spun round. Meaning that the door was already open. He hesitated, listening, then called out to his sister, who was supposed to be away and was not usually someone who made sudden changes of plan. There was no reply. He sensed there was the odd stillness, as well as silence, about a place that is empty.

The flat had a hallway which led, to the right, into the kitchen-cum-sitting room. Cat’s bedroom was on the left. Simon had a curtained-off area which was not as poky as he had assumed when first seeing it – there was room for a small double bed, chest of drawers and table, as well as a hanging rail for clothes.

He took a deep breath and his body relaxed fully for the first time that morning.

There was barely a sound, as his arms were grabbed and held behind him in a lock, and he felt a pressure in the small of his back which could only be coming from a gun.

Swiftly, efficiently, he was blindfolded and pushed into the corridor, to the stairs, down, out through the doors.

The car must have pulled up, once he had been seen entering the building. He was shoved into the back seat and someone climbed in next to him.

No one had spoken.

‘I have police monitoring me the whole time. They’ll be aware of everything. I can hit the panic button upon my belt.’

No reply.

The car started and immediately picked up speed. There seemed to be no traffic delaying them, so Simon assumed they had hit the dual carriageway heading west. He cursed his own incompetence and lack of caution, and that he had not thought ahead. Either he had been followed or they had known where he lived. The former seemed the most likely, but it was only a guess.

Now he was in the hands of God knew who, except that they were dangerous, determined, ruthless and would want him out of the way and silenced.

The car took a roundabout fast. His stomach had been knotted since they had come up behind him and now the knot became violent nausea. He turned his head to the left. If he was going to throw up, it would give him satisfaction to do so in the lap of whoever was sitting next to him.

He was in a room with bare hard surfaces, so that every sound, their footsteps, the bang of the door, the scrape of chair legs, was unpleasantly loud. When he was pushed into a chair his hand touched the edge of a metal table.

‘I need a drink. I badly need some water,’ he said.

‘Help yourself.’

And the blindfold was off and he saw a jug of water in front of him. He was so thirsty he drank two glasses straight off, before even glancing around to see where he was.

Or who was in the room with him.

‘Better?’

The voice was slightly familiar.

‘First thing I’m going to do is apologise, Simon. Not strictly necessary but you’re entitled to it.’ Nick spoke. John was sitting next to him, plus DI Bartlett, from his own station, on the other side.

‘Speechless? I’m not surprised.’

He was. He struggled between astonishment and relief but within seconds both were submerged under fury. He opened his mouth to let out the protesting expletives that formed but knew he had better remain silent.

‘You can say it,’ John said, smiling slightly. ‘We’ve heard it all, and like Nick said, you’re fully entitled to a blast-off.’

‘So this was a set-up? Just a bloody set-up?’

‘We call it a training exercise. You might recall that I said you were being looked at and we came in to take it one step further. Try you out, see how you performed, whether you go forward – and upward eventually – or stay comfortably in your helmet and boots for another year or three and then transfer to CID – starting on the bottom rung.’

Simon drank a third glass of water and waited. He had messed up at the end, though so far as he remembered he had done the right things at the start, but he had not covered himself in glory and the bar would be set high. He was angry with himself now, not with them, and that made it easier to say what he felt.

‘I know it doesn’t change things, and I’m not making excuses but I don’t think I got everything wrong. Is there a chance of being put through this again at some point? Obviously it would be different, I’d have to be completely in the dark, I’ve no idea how that could be done, but I’m sure you would know. Can I get another stab at this?’

There was a silence. The three men opposite him did not look at one another.

Then Nick said, ‘No. You can’t. You don’t need it.’

‘What he means is, you did very well. You got yourself out of a couple of tricky situations, you used your initiative, you thought on your feet and did it quickly, you weren’t afraid to change your mind or question the situation. True, you made one or two elementary mistakes, but there isn’t a single one of us who hasn’t done that. You behaved sensibly, you assessed the risk, you didn’t take anything for granted. You made the right checks, and the right calls … it’s not easy. We’re happy, Simon.’

He felt numb and couldn’t take in everything that had been said, only that he’d passed whatever test it was.

‘Thanks,’ he said. ‘That’s … thanks. So now what?’

But John and Nick had stood up and were pushing their chairs back.

‘No idea,’ Nick said. ‘You carry on as usual, you’re still uniform. For the time being, nothing changes.’

‘Right. So …’

‘And thanks,’ John said over his shoulder, when they were both half out the door.

Only the DI was left, leaning back in his chair and looking at Serrailler. Simon looked back.

‘Good work. Takes a bit of getting used to.’

‘It bloody does. Can I ask if –’

‘– if I have any idea what will happen and when? No. They don’t tell me anything – at the moment they probably don’t know themselves. These things often come from left field. But it will happen and you’ll find yourself in the thick of it, which I guess is what you want?’

He got up and went to the door.

‘Good luck.’

Serrailler stayed behind after the door had closed. Around him, the everyday sounds of a police station at work, but in here he felt as if he were in a bubble, alone, without being required to do or say anything, except to reassess what had happened and try to guess what might. It was daunting. Exhilarating.

The sun slanted through the window and covered him and he stood for some time, looking out, at the sky and the rooftops, and at his own future.

Prologue

For a long time, there had been blackness and the blackness had no form or shape. But then a soft and cloudy greyness had seeped in around the edges of the black, and soon, the images had come and these had moved forward very fast, like the pages of a child’s flip book. At first he could not catch any, or distinguish between them, but gradually their movement had slowed and he had made out faces, and parts of bodies – a hand, a thumb, the back of a neck. Hair. The images had begun to pulse, and balloon in and out, like a beating heart, the faces had swirled together, mingled then separated, and once or twice they had leered at him, or laughed silently out of mouths full of broken teeth. He had tried to back away from them or lift his arm to shield his eyes, but he was stiff, his arm heavy and cold, like a joint of meat taken out of the freezer. He did not know how to move it.

The faces had split into fragments and begun to spin uncontrollably, and he had been looking down into a vortex.

A flash of light. Inside the light, millions of glittering, sharp pinpoints. Another flash. The pinpoints had dissolved.

Simon Serrailler opened his eyes.

It was surprising how quickly things had fallen into place. ‘What day is it?’

‘Thursday. It’s twenty past five.’ The nurse turned from adjusting the drip to look at him.

&nbs

p; ‘When did I come round?’

‘Yesterday morning.’

‘Wednesday.’

‘You’re doing very well. How do you feel?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘Any pain?’

He considered. He moved his head and saw a rectangle of pale sky. The roof of a building, with a ledge around it. Nothing seemed to hurt at all though there was a strange heaviness in his left arm and neck. The rest of his body felt slightly detached. But that wasn’t pain. He remembered pain.

‘I think I’m fine.’

‘That’s good. You’re doing very well,’ she said again, as if she had to convince him.

‘Am I? I don’t know.’

‘Do you know where you are?’

‘Not sure. Maybe a hospital?’

‘Full marks. You’re in Charing Cross ITU and I’m Sister Bonnington. Megan.’

‘The nearest hospital isn’t Charing Cross … it’s … I can’t remember.’

‘You’re in west London.’

He let the words sink in and he knew perfectly well what they meant. He knew where west London was, he’d been a DC somewhere in west London.

‘Do you remember anything that happened?’

He had a flash. The body parts. The hand. The thumb. The mouth of decayed, broken teeth. It went.

‘I don’t think I do.’

‘Doesn’t matter. That’s perfectly normal. Don’t start beating your brains to remember anything.’

‘Not sure I’ve got any brains.’

She smiled. ‘I think you have. Let me sort out your pillows, make you a bit more comfortable. Can you sit up?’

He had no idea how he might begin to do such a thing, but she seemed to lift him and prop him forwards on her arm, plump his pillows, adjust his bedcover and rest him back, without apparent effort. He realised that he had tubes and wires attached to him, leading to machines and monitors and drips, and that his left arm was in some sort of hoist. He looked at it. Bandages, a long sleeve of bandages, up to his shoulder and beyond.

‘Is that painful?’

‘No. It’s sort of – nothing.’

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

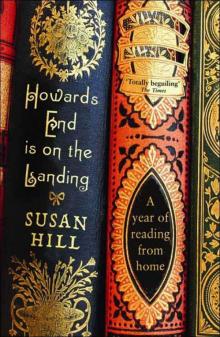

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing