- Home

- Susan Hill

The Comforts of Home Page 4

The Comforts of Home Read online

Page 4

‘Oboe?’

He gave Kieron Bright, his stepfather, a long-suffering look. If he forgot everything else, he would never forget his oboe, the instrument he had taken to so readily that it seemed to have become an extension of his body within a few months.

‘And go!’

Kieron’s route into the police HQ at Bevham did not take him past the cathedral, but from the first days of his marriage to Cat, he had offered to drive Felix into his early choir practice.

‘It’s perfectly simple,’ he had said. ‘It means I have Felix to myself every morning. It gets me into work first thing. It means you don’t have to do it, and if it’s a bit out of my way, it’s a lot out of yours to the surgery. Sorted.’

It made sense, but for her the best reason was not the obvious and practical one. Her husband wanted to bond with her younger son and Felix seemed quite happy with the arrangement – though Felix was happy with most things. He was a contented, settled child who took life as it came, enjoyed what it offered and had barely given her a moment’s anxiety.

Hannah, away at her performing arts school, had grown from a troubled child into a talented young girl, who shared Felix’s easy-going cheerfulness. Sam, her eldest, was the difficult one.

She watched the car turn out of the drive, her son turned towards Kieron, chatting eagerly, then swore mildly that she had forgotten to remind them that it was her night for St Michael’s Singers rehearsal, the first of the new season. Would Kieron remember that he and Felix were home alone for supper?

Kieron would. Her reminder to him would have been redundant. He was Mr Organised, Mr Tidy, Mr Efficient.

He was also the husband she had never looked for or expected to have, after Chris’s death. They had certain traits in common, as she had always recognised, but organised was not one of them. Only in his GP’s surgery had Chris been that. But his dedication and commitment to the job had been the same, and Cat respected it, along with the fact that often those jobs took first, second and third place, before her. She would not have had it otherwise. Besides, she thought now, going upstairs to put on her make-up ready to face the day, she had often put her own career first and it had not always made for an easy family life. When she had been a GP, before the new regime which had taken away their obligation to do nights and weekends on call, she had been stretched between her patients and her children, and only the fact that Chris had been a doctor too had made it acceptable. When she had been medical director at Imogen House, the Lafferton hospice, she had also been in the middle of conflicting pulls of loyalty and duties.

Now, she was a part-time GP again, no longer a partner. Had it all been the wrong way round? With two of her children away from home for much of the time, and a husband to share her life and the domestic round, she should have been giving more hours to her work, not fewer.

But writing a book on palliative care in general practice was filling the hours she had saved and she planned to write more. Both her parents had been hospital doctors, and had lectured, researched and written. She was following in the family footsteps.

Unlike Si, she thought, pulling the mascara wand out of its container. She must email him later.

And then there was Sam to contact, Sam up in Newcastle, ostensibly to help a friend settle into the university, but more, she suspected, to get away from home and the need to make decisions about his own future – and possibly away from his stepfather, though about that she was undecided. Kieron had said everything was fine between them, but that it would all take a while to shake down. Sam had said nothing.

At their wedding he had been quiet but cheerful enough. There had been only the families and a handful of close friends, and it had been held in the small Lady chapel of the cathedral. She and Kieron had decided from the beginning that she would not be given away by anyone, but that they would present themselves together, as equals. Also from the beginning, her father had said that he would not attend. Simon had not recovered from being at death’s door following the attack, losing his left arm and spending several weeks in hospital. He had seemed pleased, but reserved and still slightly shell-shocked. It had been a good day, Cat had had no doubts about marrying again, but was glad when it was over and they could settle down into everyday life, after the few days in New York with which Kieron had surprised her.

She finished her make-up, flicked a brush through her hair again, and left for the surgery, very conscious that she had none of her old enthusiasm for the job. It was not the same. The crisis in general practice had cut deep into everyone’s sense of dedication and passion for looking after patients, who, in their turn, had become disillusioned with doctors and the service they received, and, as a result, more demanding and more liable to complain.

She found a piece of paper on her driving seat.

Chin up. It’ll be a good day. Love you. K.

He left notes like this, not every day, when she might come to take them for granted, just at random, a Post-it note stuck on her mirror or the pillow, a sheet torn from a notebook, as today, in the car. She slipped it into her bag, smiling as she drove off.

As she walked into the surgery, she saw a familiar figure at the front desk. Mrs Coates, eighty-nine and frail, a long-term sufferer from arthritis and polymyalgia, more recently recovered from pneumonia, and with failing sight. She lived alone, had been indomitable, but, Cat thought, had had enough of struggling with life by herself.

‘I do understand,’ she was saying now to Angella, one of the receptionists, ‘I do know how busy you all are. I do know that.’

‘So, I’ve got an appointment with Dr Sanders on Monday week at two thirty. Will you have that?’

Cat did not want to interfere and undermine Angella, but as she slipped past, Mrs Coates turned round.

‘Oh, Dr Deerbon, I do understand how it is, but I’ve been trying to get to see you and you’re always so busy, there’s never anything available. And it’s so difficult seeing a different doctor every time and having to start all over again explaining, although I know they’re all very good.’

‘I was trying to tell Mrs Coates that you all have her notes in front of you, it really doesn’t matter who she sees.’

‘I know. May I have a look?’

A quick glance at the appointments screen showed her what she already knew, that she was full at every surgery for the next two weeks, which was as far ahead as patients were allowed to book. Like Mrs Coates, she understood. The new system meant that patients took whatever appointment was available with whichever doctor of the seven. That was fine for the person with a strep throat or a child with a rash – any doctor would serve. But for older patients, or those with a long history about which one doctor knew a great deal, or for the people who felt uncomfortable talking to someone strange, there ought to be the facility for them to choose the GP they preferred.

‘Is it about something new, Mrs Coates? You don’t have to go into it all here, but just say if you want to talk about something recent or something ongoing?’

Angella was looking furious.

‘It’s not new, Doctor, it’s …’

‘Can you come back in at ten past one? I’ll slip you in then.’

Surgery ended at twelve thirty, but generally overran by twenty or thirty minutes.

‘I’m sorry to ask you to come back but I really am packed out this morning.’

‘That’s very good of you, Doctor, very good. No trouble to come back then. Thank you. I do understand how difficult it is, I do understand.’

‘I know you do. I’ll see you later.’

The reception area was filling up, the phones were ringing. Angella gave Cat a filthy look. I understand, too, Cat thought. Only too well. But rules have to be bent. She was not going to be bullied into apologising.

She logged on as the first footsteps came down the corridor to her surgery. There were still plenty like Mrs Coates, who needed gentle handling. How many times had she said in practice meetings that the system ought to be a servant but t

hey were in permanent danger of allowing it to be their master?

Four

To [email protected]

From [email protected]

Good morning, Simon. Hope all is well on Taransay. Rest up. You need it. But I hope the cop in you is still raring to go when you have caught your breath. We’ll find something to ease you back in.

Everything good here.

Kieron

To [email protected]

From [email protected]

Hi Si, still in Newkybroon land. Back Monday and don’t ask then what. Gotta make plans, gotta make up mind. Need to talk. When ru home? Last match on Sat. Suppose that’s it for you now, cricket-wise. Tough. Mum sounds chirpy. Flixer ditto. Would you even know I had a sister?

Love from Sam

To [email protected]

From [email protected]

Hi dearest bro, how is it? Stunning here, 26 degrees today, wall-to-wall sunshine and Felix complaining about having to wear his blazer. Kieron still doing the school run but something has to give surely? How’s the arm? Any news on the permanent one? I know you won’t want me to mention him, but you’re going to have to put up with it – have you heard from Dad? I am pretty sure the answer will be no, and he usually wings me something curt every few weeks and he hasn’t since mid-July. Judith is coming down to stay for a few days next week and it will be great to see her but the subject of Dad will be the elephant in the room, as usual, and it isn’t easy.

Hannah’s school are doing Guys and Dolls – she sends excited messages, desperate for a good part. Warning: – we’ll all have to go.

Sam due back but not holding breath. He’s pretty unsettled. But he seems relaxed about K. They get on fine. God knows what he’s planning for this year. His A levels were fine but he seems to be having a rethink career-wise. To what, I have no idea. We can’t have that conversation at the mo. He’s even mentioned med school once or twice. Until now, it’s been police – and, even more, armed police – all the way. And he’s never been passionate about medicine, and you have to be.

I used to hope one of the three would carry on the family medical tradition but I wouldn’t wish it on anyone now, unless it was their only and complete obsession and then for some rare speciality. Neurologist fine. Facial reconstruction of war victims, fine. Paediatric oncologist, fine. General practice – not so much.

Loads of love. And Phone Home.

C

He was sitting on the end of the quay in the sun – sun which was forecast to disappear that evening, giving way to rain, gales and high seas. It was not always easy to tell how long these might last, but the chances were that when they had eased, the late-summer sun would not return, certainly not with the warmth it still held today. The boat was due in soon, carrying supplies and mail, and he wanted to help unload. He could carry reasonably large boxes and crates but not the heaviest. Not with the arm. Not as he had once done so easily. He had never prided himself on any particular muscular strength, though he had always been a sportsman, and fit. After the physiotherapy he had been subjected to in rehab he was probably fitter than ever but he had been warned not to over-test the prosthetic by lifting and carrying anything too heavy. Later, when he had the new and permanent arm. Later. He had grown used to hearing that. Later. But the physios had been the most positive of people. No. Never. Can’t. Those words had not been in their vocabulary.

He slipped his iPhone away. There had been nothing in the emails to alarm him. Sam would get there – wherever his ‘there’ might be. His sister seemed bird-happy. He had never had any real concerns about her marriage to the Chief from a personal point of view. Because he was still on rehab leave, he had not yet encountered any professional conflict over having his boss as a brother-in-law. Perhaps he never would – not only because they would both go out of their way to accommodate one another, but because he still had doubts about returning to work. How much of a cop could he be? He had been assured the arm would make ‘absolutely no difference to anyone or any aspect of the job’. Really?

He let Cat’s mention of their father slide past him. Since Richard Serrailler had been accused of rape, and managed to find a defence counsel clever enough to get the CPS to drop the case, Simon had wiped all thought of him from his mind. Their relationship had always been difficult, but that aside, he had no doubt whatsoever that the CPS had made a mistake.

He glanced out to sea and saw the ferry just turning into the harbour. A few people were gathering down there, more would appear. The pub and shop would start stocking up now on extra supplies for the coming winter, using all the storage they had, part of which emptied in the summer season, when the boats came in more frequently. Simon jumped up.

The islanders knew all about his accident, and the loss of his left arm, and there had been many a quiet word or the offer of a drink, but otherwise no great fuss had been made, for which he was grateful. Now, he waited as the boat docked carefully, the hawser was thrown from on board and within minutes the first cartons and crates were being unloaded. Simon and two others started to lift smaller cartons of groceries onto sack trucks and wheel them to the store behind the shop.

‘Candles.’ The speaker was the woman he had seen walking along the shore on the other side of the island. She was tall, and her blonde hair was tied in a knot at the back of her head. ‘You came yesterday?’ she said.

‘Evening before.’ He was finding it difficult to grip the sack truck and manoeuvre it up the slope, so did not want to waste his breath on talk, but she seemed to grasp the fact at once. She did not offer him help, just got out of his way, heaving her own truck to the top.

The unloading, fetching, carrying and storing went on for an hour. The boat was fully laden, and without passengers other than the two-man crew.

Candles. Batteries. Thick socks. Heavy-duty rubber boots. Butane-gas cylinders. Household cleaner. Drums of cooking oil. Salt. Waterproofs. On and on.

Simon stopped to get his breath. He had done a lot of exercise since his accident, but his core strength was still not back to normal and his shoulder ached badly.

‘Nearly there.’

The woman was hauling crates off the sack truck into the back of the store, making light of each one. He felt annoyed with himself. He shouldn’t be tiring before a woman. That was something that once would never have crossed his mind. Now he was resentful. His pride was hurt.

‘That’s it,’ someone shouted. ‘Last to the bar’s buying.’ There was a good-humoured rush across to the Taransay Inn.

‘Have you met Sandy?’ Douglas appeared out of the crush. ‘She arrived here not long after your last visit and she’s a fixture.’

The woman raised her glass of beer. She was perhaps in her late forties, possibly a bit younger – the wind and weather soon gave those who stayed a winter or two a rough and reddened complexion that added to their years.

‘Simon Serrailler.’

‘Sandy Murdoch.’

Simon had a large glass of malt to help numb the pain in his shoulder. He had heavy-duty meds prescribed but preferred the whisky.

‘How long are you here?’

‘A week or two or three. I’ve no firm plans.’

‘Nor had I. I came for a week, a week stretched to a month and that was four years ago, near enough.’

Her accent was not Scottish but she had acquired a slight Taransay intonation, which was a lilt unlike any other Simon had encountered.

‘How do you find the winters?’

Sandy shrugged. ‘It’s the wind can drive you mad. But I like it fine. You hunker down.’

The bar was full and others coming in had damp shoulders and hair. Rain was streaming down the windows.

‘And you?’ Sandy asked, though she did not look at him. ‘You had an accident.’

‘Yes.’

‘Car smash?’

‘No.’

‘Ah ha.’

‘Let me buy you another.’ Simon got up.

‘Bitter shandy? A chaser?’

‘No, no, I don’t drink the hard stuff much. Only to keep out the cold sometimes. But thanks.’

Kirsty had come in and was saying something to Douglas at the bar. ‘What can I get you? Douglas?’

‘No, I’m away to fetch Robbie, I’m running late and school’s out at dinnertime today.’

Sandy waved as Kirsty left, buttoning up her waterproof, hair flying.

‘Douglas?’

‘Thanks. Just the single and then I have to be away with a roll of fencing to the other side.’

When the two whiskies were pushed over the bar, Douglas topped his up from the jug on the counter. Serrailler made a face. ‘Bloody sacrilege,’ he said. ‘A good malt and you ruin it with your lemonade. I can never get my head round it.’

Douglas laughed. ‘Any news?’ He had nodded towards Simon’s left arm.

‘No, it’ll be a few weeks yet. They don’t tell me much.’

‘You going back to work before you get what Robbie calls the bionic arm fitted up?’

‘I don’t know, Douglas, I just don’t know … the job’s there, they’ll hold it as long as I want them to, but that can’t be forever.’

‘Can you not ease in gradually?’

‘I probably could. But do I want to? Go back at all, that is.’

‘What else is there?’

Simon finished his whisky and did not reply. It was a question he had asked himself many times, without being able to give himself a reply.

Douglas straightened up. ‘Thanks,’ he said. ‘Looks as if Sandy’s kept your seat warm over there.’

‘Who is she? Other than a settler. Where did she come from?’

Douglas raised an eyebrow. ‘Bit old for you.’

‘Get out, I don’t mean that and you know it. Just wondered. A newcomer who comes to Taransay and stays …’

‘Aye, well … she’s made herself useful from the start. Come to think of it, I could do with a hand with the fencing … get it finished in half the time. She turns her hand to most things. Helps out here when it gets busy in summer. Iain says she must have run a bar herself in another life. But it’s the fencing for now.’ He edged through the crowded bar to where Sandy was sitting.

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

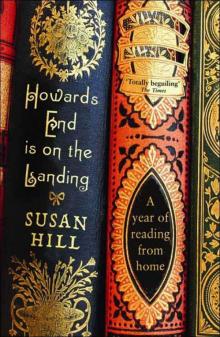

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing