- Home

- Susan Hill

From the Heart Page 5

From the Heart Read online

Page 5

‘Fog up the river … fog down the river …’

At the end of the sentence, she jumped as if someone had spoken to her suddenly. But the room was quiet apart from the occasional low murmuring of the couple to one another and the voice she had heard was in her own head.

‘You are going to have a baby. You are going to have a baby … You are … You …’

And then she saw it written up in front of her mind’s eye.

‘You are going to have a baby …’

‘Fog up the river … fog down the river …’

‘You are going to have a baby …’ The writing scrolled down slowly like the credits at the end of a film, the one and then the other.

‘You are going to …’

A clock in the hall struck seven and at once the quiet couple and the woman alone got up, and Olive got up too, and followed them into the hall, which smelled of onion soup.

Dining Room.

Pink lamps. Pink cloths. Port-wine carpet. But it was warm and not too large. One table was already occupied. The quiet couple sat down, then the woman alone. She chose the table adjacent to Olive’s.

‘You are going to have a baby,’ the menu read. A small piece of paper with typed words.

‘You are …’

Eggs Mimosa

Or

Cream of Onion Soup

Or

Fruit Juice

Lamb Cutlets

Or

Cod and Chips

Or

Omelette

(Choice of Cheese or Mushroom)

Potatoes. Mashed or Chips

Seasonal Vegetables

A waitress appeared through the swing doors with a pint of beer on a tray, and as she passed, the yeasty smell reached her. She had always liked the smell of her father’s bottled stout but this seemed very strong.

She did not feel sick but the fumes of this ale repelled her and she moved her chair a little.

‘You’re going to …’

She had brought her book.

‘Fog up the river … Fog down the river.’

The food was not unlike the food in college. She felt self-conscious drinking soup alone. But it was good soup and why should she not be here by herself?

Why was she?

She could just as easily have ended up in Cardiff or Reading. Exmouth. York. Edinburgh. Anywhere.

She had written a note to her father, saying that she had come away from London for a few days to concentrate on the books she had to get through for reading week.

She would have to leave, of course, though she might manage to the end of this term. But they would not want a pregnant unmarried student remaining in college until the end of the year. She could not go home.

She could not tell Malcolm. Malcolm would panic and tell his parents and they would assume that he would marry her. They would want it. Welcome it. Penny’s death had left a gap in their lives and hearts they would be desperate to fill.

Should she tell her father?

She knew that she could never get rid of a baby, even if she had had the least idea how anyone went about it. It had been her first certainty. So, people would find out, inevitably. She would not have to tell them.

Treacle Sponge and Custard

Or

Sherry Trifle

Or

Cheese and Biscuits

Tea or Coffee

She did not eat very much and she was first back to the lounge beside the electric coals, before the others.

She could ask Margaret Reid – now Margaret Donner. Or even Mary. They had always had answers and information, between them.

But not about this.

‘Fog up the river …’

Presumably she ought to see a doctor before long.

Just not Dr Bonney.

So, here then. She could say that she was moving to live in this town. Find the address of a house to rent. No one would know her.

The door opened on the quiet couple, with the woman alone behind them and she glanced at Olive, glanced again, and came to sit near her. Olive got up.

‘Please, have this chair. It’s the warmest place. I’m going to my room now.’

‘I wouldn’t dream of it, I’m fine here. Aren’t you staying for coffee? Do stay. It’s better coffee than you might expect.’

Olive subsided into her chair, not knowing how to refuse without seeming rude. And why would she want to refuse? But she did not want to give off the smell of loneliness. The coffee came in a metal pot with a scalding hot handle and cups which were fluted round the rim.

‘You’re rather young to be holidaying alone.’

‘I’m not … I mean, it isn’t a holiday.’

‘Oh?’

‘I’ve just come for a few days of quiet – to work.’

Without saying anything, the woman seemed to be urging her on, her face full of interest. Apparent interest?

‘I’m doing a degree. In London.’

The bright, interested look was like make-up, not altogether convincingly applied.

‘It’s reading week.’

She had not meant to stammer on and the woman waited, but Olive drank her coffee, keeping the cup to her lips after she had swallowed and her eyes on the electric coals.

The door closed on the quiet couple.

‘How long are you staying then?’

The woman had a pleasant, soft voice, and fair hair fading to grey, hair that stood round her head in a halo.

‘How old are you?’

It seemed a rude question, even before the woman had given her name and asked for Olive’s, but she did not apologise, just waited for a reply.

‘Twenty-three,’ she lied.

‘Will you have a liqueur with me? We can order what we want from the bar and they’ll bring it with more coffee.’

‘No,’ Olive said, standing up. ‘Thank you but I need to get some work done now.’

‘Oh, surely not! It’s after nine o’clock.’

‘All the same. And I have to ring my fiancé.’

‘Really?’

She doesn’t believe me. The way she looked at me through narrowed eyes.

She doesn’t believe me. What does it matter?

Olive turned at the door. ‘His name’s Malcolm,’ she said. ‘It was nice to meet you.’ She went, without seeing the woman’s expression.

Why had she done that? What had worried her?

She leaned against the door of her room, as if afraid someone might try to open it.

Why had she said that? My fiancé. Malcolm.

The woman had tried to be friendly. She was lonely, that much was obvious. There had just been … what?

She went to run a bath and the noise of the water splashing drowned out her thoughts and the woman evaporated into the steam.

She lay down and looked at her stomach. Touched it. Her own body was strange and alien to her. She looked the same but she was no longer her own self, the self she had lived in intimacy with since birth. She was no longer that person.

She turned on the taps again and let them run until the water had covered her almost to her neck.

The sea was turning over and over within itself moodily, but there was no gale this morning and no waves crashing against the wall.

She would not have gone into breakfast. She wanted to find a telephone directory in the booth in the hall, but as she walked across, the quiet couple were just ahead and the man held the door, smiling at Olive, and so she had to go in. The dining room looked shabbier in the morning light, without the gold curtains and the pink shades. She asked for tea and toast.

‘Nothing cooked? Nice bacon today.’

She shook her head and opened Bleak House.

‘It’s quite ordinary bacon,’ the woman alone said, ‘actually.’ From the adjacent table.

Olive smiled without looking at her. Beyond the bay windows, a boy on a bicycle went past slowly, making hard work of the pedalling. The windows had a fine gauze over the glass whi

ch looked like dirt but she thought must be sea spray.

Her pot of tea came, and the toast cut into crustless triangles.

‘And how was the fiancé? Malcolm?’

She should have been wearing a ring, of course. That is what people did when they were engaged to be married. She nodded and concentrated on buttering toast.

She had no idea how much money she had in cash. Would the hotel accept her cheque? Perhaps she ought to ring her father.

‘You’re not in any trouble, I hope.’

The woman alone sounded amused. What did she think, that Olive was a prisoner on the run? But she was right. ‘In trouble.’

‘No.’

‘Good.’

Knives scratched plates and the kitchen door swung open, wafting in the smell of frying.

Her father would worry but he would send money. That was the easy part.

‘Do you have the address of a local doctor please?’ she asked the woman at the front desk.

‘Oh dear – aren’t you feeling very well, Miss Piper?’

‘No – yes … I’m all right … I just …’

‘No, no, none of my business … so long as it’s nothing serious.’

Nothing serious.

Nothing serious?

The woman handed her a slip of paper.

Drs Marshall and Tait

30 Cliff Road

Phone 7713

‘The phone box is there but you can just go. Surgery’s every morning from nine till half eleven.’

The cliff path was steep, and halfway up, she felt giddy and had to sit on a wall. When she got there, she waited an hour.

Dr Tait. He wore a tweed jacket and a pipe smouldered in an ashtray on his desk. The smell nauseated her.

‘I think I may be … I think I’m pregnant.’

‘What makes you think so?’

‘I’ve missed two periods.’

‘Doesn’t necessarily follow of course but if you’re usually regular …’

‘Yes.’

‘Anything else? Nausea? Tender breasts?’

‘Not really.’

‘So, you had unprotected intercourse? Or was this what is euphemistically called “an accident”?’

‘No … not … not really.’

‘And you’re how old?’

‘Twenty-seven.’ She did not know why she lied. Perhaps she wanted to seem mature. But in that case …

‘Not a teenager then. So why didn’t you take precautions? You seem an intelligent young woman.’

‘In the end … I mean … He …’

‘That’s right, blame the young man. But you’re the one left holding the baby, you’re the one who should have been responsible. Unless you were raped. I take it you weren’t raped?’

Why did he ‘take it’? She felt angry but there was nothing she could say other than ‘No’.

‘All right … so, what do you want me to do exactly?’

Olive did not know what to answer.

He sighed. ‘There’s no point in sending away a sample for a test – too early. Wait until you’ve missed period three and then come back – you never know, you might not.’

‘Is …’

‘Is?’

‘What will happen to me?’

‘Well, you’ll have a baby, my girl, that’s what will happen. Do you have family?’

‘My father … my mother’s dead. I’m an only one.’

‘Not ideal then. And what does your father say?’

‘I haven’t told him.’

He sighed again but then leaned forward. ‘Now listen, my dear … whatever you do or don’t do, I beg you not to drink bottles of gin in hot baths, or jump off tables … never works. Or, more seriously, do not visit backstreet abortionists with knitting needles. And they still exist, they still exist. Don’t do it. People die. Get married. Or not – it’s up to him. Have the baby, and if you’re still on your own, have it adopted, give it a better life from the start. Being an unmarried mother isn’t any fun. Give someone what they long for and can’t have. Understand?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good girl. You’ll be fine. All right?’

‘But the thing is … where would I go?’

‘There’s a pretty good cottage hospital here – good midwives and this practice looks after it.’

‘No, I meant …’

He picked up his pipe and began to tamp down the tobacco with his forefinger. ‘What did you mean?’

‘Aren’t there places for …?’

‘Homes for unmarried mothers and their babies? There are. Not here. But there’s St Jude’s in Tremear. They’re good. From what I hear. You could go and look when you’re quite sure. Now, my dear, I am guessing there’s a full waiting room … Come and see me in a month’s time.’

14

‘I’M SORRY – I should have let you know. I didn’t think.’

Home was home but she usually did let him know in advance, though not because she felt it was required of her.

Home was home.

Wasn’t it?

‘My dear girl, it’s absolutely fine, how could it not be? It’s just a surprise – a very nice one, of course, that goes without saying. Have you had any lunch?’

‘It’s five o’clock!’

‘Is that all the luggage you’ve brought? Just the weekend then?’

Olive looked with surprise at the duffel bag beside her. Yes. All the luggage. It didn’t seem to matter.

When she came down again from unpacking what she had – Bleak House on her bedside table – her father was in the kitchen. She saw vegetables prepared and cut up in a pan of water, potatoes peeled.

‘I need to talk to you.’

He looked hesitant, ruffled, as if she had caught him out in something.

‘I’ll put on the kettle.’

She wandered into the dining room. The best white cloth on the table. Glasses. Tumblers. The canteen of silver cutlery open.

Her father stood behind her. ‘Come and have your tea. I can explain.’

It was not that she minded, or was upset, or hurt, not that she disapproved, not anything but a complete surprise.

Her name was Peggy Drummond, her father said. He had been taking the train to London and it was half an hour and then forty minutes late, and so, instead of remaining on the platform talking to the woman sitting next to him on the bench, he had suggested they go into the warm buffet. They had drunk coffee, and then gin and tonic, and, inevitably, got into the same compartment. At Paddington he had put her into a taxi and taken the one behind, as they were going in opposite directions.

He had thought very hard before looking her up in the telephone directory when he had returned home.

‘We have met two or three times – outings, you know – but then it occurred to me that I should test my cooking skills. I have been practising – I must say, I rather enjoy it.’

He had often looked troubled, or harassed, and now he did not. His face was the same – of course it was. And yet it was not.

‘But you said there was something you wanted to tell me, Livi. You can talk while I separate some eggs.’

But separating and then whipping eggs meant him fussing about and making a noise and how could she possibly tell him now?

How could she possibly tell him?

Peggy Drummond arrived precisely at seven. By then, he had changed his shirt and tie, and was hovering between the kitchen and the hall. Olive watched him.

She was a large woman, well corseted, her hair blonde, puffed up and stiffened, like candyfloss on top of her head. A two-piece purple suit with a shiny finish.

She talked. She had been a buyer in a large city department store for twenty-three years. Two husbands, the first dead of heart failure, the second of liver cancer. No children.

‘I never wanted them. I’m not maternal. I enjoy my job and I like a social life. I have always been keen on the theatre … that was where I was going when I met Ralph.�

��

Two years earlier, she had opened a boutique.

‘Nothing really for you, Olive, as a student, more for the middle-aged woman with a bit of pocket money. Still, if you do come in and see something you like, I’d always give you a bit of a discount.’ She turned her head. ‘She doesn’t take after you, Ralph.’ As if Olive was not there.

No. Nor her mother. Well, perhaps her mother a little – the high forehead and small mouth were from Evelyn.

He went in and out, carrying the best china vegetable dishes with an oven glove, seeming slightly in awe of Peggy Drummond. Or puzzled by her.

‘This is wonderful, a man who cooks. I’m afraid I loathe cooking, I live on salads. Do you cook, Olive? No, I imagine you students are catered for?’

‘I cook when I’m here.’

Another dish came in. Three vegetables, plus potatoes. Her father pulled off the cap on his bottle of stout, and at once the smell made Olive turn her head away, then get up quickly and leave. Her father continued to fiddle with lids and serving spoons. Peggy Drummond seemed not to notice.

She was not sick, only nauseous. She took some deep breaths, drank water, but when she returned to the table, felt no better. It was hard to force food down her throat. After another half-hour, she left them, to lie in bed on her side, which gradually eased the sickness and she fell asleep.

‘My dear girl, how are you feeling? I’ve made tea and toast … do you feel up to an egg? Or grapefruit. I have rather taken to grapefruit lately.’

She drank four cups of tea and then, suddenly ravenous, ate two boiled eggs and a quantity of toast. Her father watched her, beaming encouragingly, as if she had been an invalid for weeks and was now showing faint signs of recovery.

‘And Peggy now?’ he said with a touching eagerness, looking at Olive for approval. For reassurance?

‘Yes,’ she said and filled her mouth with toast.

‘She has been very … you see, I think she’s good for me. I was growing old before my time, Livi. I didn’t go out except to the Lodge. I was becoming a bit set in my ways.’

‘Do you go out now? With Mrs Drummond?’

‘She did ask you to call her Peggy.’

‘Sorry. Do you go out much with her?’

‘We do go to the theatre. Occasionally to the cinema but there isn’t often much of appeal there. And – and we dance.’

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

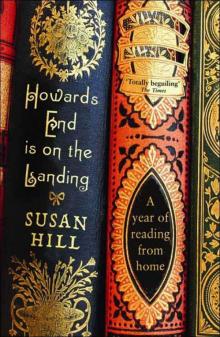

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing