- Home

- Susan Hill

Jacob's Room is Full of Books Page 6

Jacob's Room is Full of Books Read online

Page 6

The Writer’s Voice is short and packed with good things. Alvarez illuminates Donne, Coleridge, Sylvia Plath in a sentence or two as revelatory as a scalpel. Afterwards you read those writers yourself with a new and different view and understanding. And he is as good on novelists as he is on poets.

There are some writers for whom writing is a charm against an intolerable reality, and for them the differences between the lived facts and the imagined story are greatest when the two are almost identical. Jean Rhys, for example, had artistic imagination and no invention at all: she couldn’t dream up situations she herself had not been in, the people in her stories were the people she knew, and a great deal of what she wrote in her diaries she rewrote in her novels.

Another moment to pause and wonder all over again whether this matters. If the reader does not know that Jean Rhys wrote her own life over and over again in her novels, but assumes all of it is indeed invention, does that make any difference? Transmuting the lived life into fiction, many years later, is as great a skill as imagining and inventing lives and characters and events. Does it make any difference to me to know what I know about Rhys and the way she worked? I can never completely make up my mind. I do know that what applies to much else applies to fiction – that it will all be the same in a hundred years time. With novels, make that two hundred.

APRIL

I ALWAYS TRY AN APRIL FOOL joke on Facebook and it is generally uncovered within seconds, but I did have one triumph a few years ago, when I said I could now reveal that I had been appointed to write the official biography of Her Majesty the Queen. The excited congratulations lasted until after noon, when I pointed people to the date. Most satisfying.

THE BLACKTHORN IS WHITENING the hedgerows, but the weather is having its joke this year. April often comes in with bitter winds and sometimes snow, too, so that we have ‘a blackthorn winter’. This year, there is sunshine all the way. Warm sunshine.

NO HEDGEHOG YET. Just too cold. When we had our tortoise, Clarabel, we watched for her to emerge from about now and year after year she did – and then dived back under the covers again for another few weeks of snoozing. It was from Clarabel that I learned that a tortoise can distinguish between colours. If I put a tomato or a strawberry out on the grass she would trundle over for it. If I put out something green – lettuce or a few cabbage leaves – she might eat them when she came upon them but she did not make a beeline for them. She was the easiest animal companion ever, undemanding, enjoying a bit of company, but equally happy with solitude, requiring no walks or balls or squeaky toys. She was vegetarian, lived in harmony with everything else that shared the garden, and slept as deeply as a Moomin for half the year. When we sold the cottage to friends, we knew that we could not take her with us, as our new big garden would not have been safe for her for five minutes. We did not sell Clarabel to the new cottage owners, we gave her to them on permanent loan. They sent us a news bulletin on her twice a year and when she failed to emerge one final spring, they told us straight away, in a very kind and sensitive e-mail. Perfect.

I ALWAYS THINK of my rarely met but always loved friend, Miriam Margolyes, whenever I look along the Dickens shelves. She says that she was born to play Mrs Gamp, and her Dickens’ Women show was a triumph. She has often suggested I should write something for her and at last I came up with an idea she loved. I will not say what it is, in case I can give it a new lease of life somewhere after all, but when an excited producer put it to the Head of Drama, that illustrious personage waved a hand. ‘I don’t do monologues.’

Lots of great stories about Miriam go round, all of them true. The most recent is about a trip to India. She and a group of theatre management folk were sitting in a resplendent hotel foyer when Miriam happened to see a woman come in through the doors to the reception desk. ‘My God!’ she said, in tones of great awe. ‘Look! That is one of the most beautiful women I have seen in my entire life. Possibly the most beautiful woman.’ Whereupon she leaped up, went over to the woman and said, ‘I have to tell you that you are the most beautiful woman I have ever seen in my entire life. Who are you?’

The woman smiled a beautiful smile at her. ‘Well, thank you! My name is Joan Baez.’

MOLES, MOLES, MOLES. They leave their neat soil mountains on the lawn. I refuse to have anyone trap or beat them to death, but I want to urge them to build their heaps in the field on the other side of the wall. I bought a dozen solar mole spikes – and they are not cheap. You stick one into the middle of a mole hill and, once charged up, it emits a sort of buzz or soft screech which hurts the moley ears and they flee. It worked a treat last year, but now the moles are back and preferring the lawn again. For a few days the moles ignore the spikes – maybe they have not taken in enough solar power to build up to full pitch. But then we have three sunny days and even from the kitchen I can hear the massed bands of mole deterrents tuning up.

They’ve gone! On the other side of the wall, in the field not the lawn, I see a little flotilla of freshly dug mole hills.

But I am keeping the solar spikes out in the sun to re-charge, just in case. The soil the moles dig up with their strong paws is very fine, if you sift it through your fingers. You can use it for seedlings straight away.

A lot of creatures live strange lives, and none stranger than the eel, but moles, in their solitary, industrious blindness, come close.

Moldy Warp features in the Little Grey Rabbit series of children’s books by Alison Uttley. I sent the first one to Lila and, assuming that it would be a nice gentle bunny story, Jess began to read it to her at bed time – only to discover that it is about Little Grey Rabbit cutting off her own tail and giving it away.

I AM BACK to Edith Wharton.

What an extraordinary woman she was. I had never heard of her until someone told me they had been to see the film of The Age of Innocence. I am not one for film adaptations of novels, so I got the book instead, and from page one I was hooked, and went from that to The House of Mirth and The Custom of the Country. There was once a fat Penguin paperback containing all three, but of course they let that go out of print. The middle title is the master piece – but that is not to leave the others far behind.

I knew nothing about Wharton. I assumed these novels were all she had written, yet something was bumping about at the back of my mind. I discovered Ethan Frome and disliked it. Others think it a small work of genius, but there is something stark and cold about it and it did not ring true to me because it is set in rural America and, above all, Edith was a city woman. Still, it is regarded as a great short novel, so I am probably wrong.

The thing went on bumping about in my mind but there was no clue in any of the Old New York trio. I had to wait until I got back home and wandered from room to room, shelf to shelf, before coming upon what I did not know I was looking for. The Ghost Stories of Edith Wharton. I remembered them as soon as I opened the book, but the name had never connected in my mind with the author of The House of Mirth.

Her life was remarkable, especially for a woman of her time, but not knowing anything about her does not detract from the fiction because it is not autobiographical – though the Old New York she writes about was the one she and, to a greater extent, her parents knew so well. No, Edith Wharton is a fascinating woman because she is a fascinating woman. You could find much interest and enjoyment from reading all about her in the good biog raphies without reading a word of her fiction, and there are coffee table books about the gardens she created, and about her interior design, mainly but not only for her own houses in both America and France. That was unexpected. But there is more.

If you are born into an aristocracy of whatever country, you are an aristocrat for life. You are rooted in a society to which so many aspire to belong and which has formed your taste, manners, beliefs, assumptions, for good, no matter where else you may travel to or in what other country you may settle. It is important to remember this in order to realise just how extraordinary Edith Wharton’s life turned out to be, and how unli

ke most of her own class she became. Yet she remained one of the aristocrats of Old New York in spite of leaving America for Europe often – she worked out that she had crossed the Atlantic more than sixty times – eventually to remain. Through family marriages, she had connections with all New York society. But she was one of those children who are unhappy not only in their own families and backgrounds, but even in their own skin. She was destined to fulfil herself as an adult but her early years were unhappy, because she was bright and noticed things, and because her mother was cold towards her. She loved her father deeply, but he was a weak man who vacillated when she asked him to stand up for her against his wife, who even forbade EW from reading novels until she was married.

Her first marriage was less than happy because her husband had inherited what we would now called clinical depression. But they established houses, Edith began to write and, eventually, they went abroad for the first time. It was her awakening. She took an intelligent and passionate interest in European houses and interior, and in gardens, which, together with her increasingly successful writing, were to remain her lifelong study and delight.

The House of Mirth was the first of her novels to become a bestseller. After that, she, who had always lived prosperously thanks to a private income from family trusts, now became rich from her own work.

When she and Teddy Wharton were eventually divorced, she re-married, though not before she had fallen in love with another man and begun to engage with the great literary figures of the day, most especially Henry James. Her novels are often compared with his and he became her staunch admirer, but whereas his fiction became denser and more difficult to read as he grew older, Wharton’s was always more straightforward. She was a great student of human nature. She understood women, but she also knew an unnerving amount about men. She writes about social ambition, social aspiration, social climbing – the nuances of society, and about the cruelty with which it can appear to accept, only to exclude and cast off, any who are not within its charmed circle by right of birth, or at least of marriage. The story of Lily Bart, in The House of Mirth, is about society, but essentially it is a deeply felt human tragedy.

Already, then, Edith Wharton lived a full, varied and even adventurous life. But more and more surprises were to come. She was living in Paris when the First World War broke out and very soon afterwards, in August 1914, she opened a sewing workroom for thirty unemployed women, feeding them and paying them a modest wage. The thirty soon doubled to sixty and their work was in demand. She established a hostel for Belgian refugees, and organised the Children of Flanders Rescue Committee which eventually looked after almost a thousand child refugees who had fled their towns after they had been bombed by the German army. With her friend Walter Berry she even travelled by car to the war zone, coming within a short distance of the trenches, in order to see at first hand what conditions were like. She compiled and edited a book in aid of war victims, prised money for them out of wealthy Americans and was awarded the Légion d’honneur by the French government. And all this time she continued to write novels, essays, stories – and kept up a large correspondence.

She never returned to live in America. France was her adopted country and she remained there, though travelled about, mainly to Italy. She went on studying European interior and garden design, she wrote an important book about the former, and created wonderful gardens at her own homes.

Who would have expected this woman, this fine, perceptive, quintessentially American member of an elite society, as well as a major novelist, to have been so involved with and successful at helping war victims so practically in another country, and to have such an eye and taste for two very different forms of design?

I take down the best biography of Edith Wharton – by Hermione Lee – which I have had on the shelf since its publication, and skim through it again. Worth knowing, is Mrs Wharton, even without the fiction. And of how many writers can that be said? Yes, the Brontës; yes, Dickens and a few others.

She is inspiring, I think as I put The Age of Innocence down on the table, having finished it yet again. She encourages one to do so much more, be so much more.

Still, in the end, the novels have it. They have enriched me over thirty years. I can’t say that about every book I have ever opened.

WENT TO PICK UP a prescription. The doctors’ surgery is across a meadow from the steam train station (there are some diesels, too). The line runs from Holt to Sheringham, via Weybourne – and from it there are beautiful views of coast and sea. As with all of these privately run, manned-by-volunteers lines, there are all manner of special steam events – the Santa Train, the annual 1940s weekend. But it is good to travel on an ordinary day, to get a real sense of how steam was all through my childhood. The super Scarborough to Whitby line was my favourite – that track was taken up, though there are one or two nostalgia tea-rooms where station platforms used to be. The train across the North York Moors from Pickering and Goathland still runs as a tourist attraction, though, and it is a joyous sight to see it trundling across the horizon, steam puffing out into the summer sky. I loved travelling by train as a child and I still do, but steam to those of us who knew it well had an especial charm – though not so much for the railway-men, who mostly died of lung diseases caused by the smoke and coal tar, or were old at fifty, backs broken from shovelling the coal.

I remember my friend Damian whenever I see a steam train. Damian worked as a volunteer on the Tallylyn railway, and as a signalling expert for his day job. We used to discuss trains and train lines all the time, and little else – and we were in our twenties.

The last time I heard anyone refer to the old railway companies by their nicknames was in the 1970s when a friend said he was off to watch the cricket but was not taking his car. ‘I shall go by the Slow and Dirty.’ That was the Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway. LNER (London & North Eastern Railway) was Late and Never Early. LMS (London, Midland & Scottish) was Late, Mouldy and Slow. And of course the GWR (Great Western) was God’s Wonderful Railway.

Nostalgia is a delightful thing, if biased. I don’t think everything has gone downhill since the end of steam, though I am inclined to take that view re. Beeching and his axe to branch lines. (Another nod to Flanders and Swann and The Slow Train …) John Betjeman’s poems about railways remind one of how much was lost …

Rumbling under blackened girders, Midland, bound for Cricklewood,

Puffed its sulphur to the sunset where that Land of Laundries stood.

It isn’t possible to read those words from ‘Parliament Hill Fields’ without hearing JB’s voice reciting it, just as for ‘April is the cruel-lest month’, the opening of The Waste Land, I always hear in my head the version read by T. S. Eliot himself, though his voice was dry and dull, whereas Betjeman’s was rich and fruity. Both were shot through with melancholy.

With railways in my mind, I picked up a paperback called On the Slow Train Again by Michael Williams, and here is a whole section on the stations, old and new, of North Norfolk … Cromer, Sheringham – from whence still runs the Bittern Line slowly to Norwich – West Runton, Weybourne.

And here is Candida Lycett Green, John Betjeman’s daughter and one of my dearest, most missed of friends, on Cromer:

Cromer is a magical place… all red pantile roofs, cedar trees, pinnacled Victorian and Edwardian houses, flamboyant verandas on the edge of the old town … It was the arrival of the railway in 1877 which finally put the gilt on Cromer’s gingerbread.

Candida wrote that in 2010 and Cromer is still magical, though very much an acquired taste, as my mother said of gin.

THERE HAS BEEN A VOGUE in the past decade or so for pastiche Victorian detective novels set in and on and around the railways, but railway poems have been written for far longer. Such as C. L. Graves’ ‘Railway Rhymes’:

When books are pow’rless to beguile

And papers only stir my bile,

For solace and relief I flee

To Bradshaw or the ABC

And find the best of recreations

In studying the names of stations.

And then of course there is Edward Thomas’s ‘Adlestrop’. I used to live a few miles away from the village, and often make a detour just to see the famous station sign which stands on the green and the one line that always came into my head was ‘all the birds/Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire’ – Adlestrop stands on the border between the two counties. Another melancholy poem, though. Is there a jolly railway train one?

We learned W. H. Auden’s Night Mail by heart at school:

This is the night mail crossing the border,

Bringing the cheque and the postal order.

And Eliot’s ‘Skimbleshanks, The Railway Cat’ is briskly jolly. But perhaps the subject as a whole is too redolent of partings and long distant memories. Though with arrivals and meetings and reunions, too. I travel to London from King’s Lynn, via Ely – with the cathedral, ‘The Ship of the Fens’, rearing up in view – and Cambridge, though you catch no glimpse of dreaming spires from the station.

HM the Queen spends Christmas, and the whole of January, at Sandringham, in Norfolk, and travels up here from London by train in mid-December. She sits in the front first class coach with her detective, and the rest of the train fills up as normal. At King’s Lynn, the stationmaster is waiting – and there is always a photograph of him in his best suit and beaming with pride – to meet and greet her and escort her to her car. She walks a few yards up the platform and exits through the side gate, while we all pile off behind her cheerfully and go to run our tickets through the machine at the barrier. I say ‘we’ because I have travelled on her train and there is the minimum of fuss, which suits everyone. The stationmaster gets his annual moment in the sun and we other passengers feel a flush of superiority that we have just shared the same journey as the Queen. And if the train had broken down, as it sometimes does, she would have got to enjoy the fun of that, too.

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

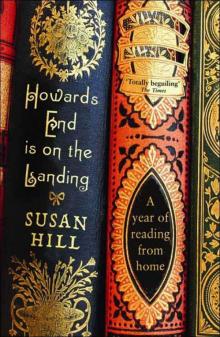

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing