- Home

- Susan Hill

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story Page 6

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story Read online

Page 6

So musing, I emerged into a small burial ground. It was enclosed by the remains of a wall, and I stopped in astonishment at the sight. There were perhaps fifty old gravestones, most of them leaning over or completely fallen, covered in patches of greenish-yellow lichen and moss, scoured pale by the salt wind, and stained by years of driven rain. The mounds were grassy, and weed-covered, or else they had disappeared altogether, sunken and slipped down. No names or dates were now decipherable, and the whole place had a decayed and abandoned air.

Ahead, where the walls ended in a heap of dust and rubble, lay the gray water of the estuary. As I stood, wondering, the last light went from the sun, and the wind rose in a gust, and rustled through the grass. Above my head, that unpleasant, snake-necked bird came gliding back toward the ruins, and I saw that its beak was hooked around a fish that writhed and struggled helplessly. I watched the creature alight and, as I did so, it disturbed some of the stones, which toppled and fell out of sight somewhere.

Suddenly conscious of the cold and the extreme bleakness and eeriness of the spot and of the gathering dusk of the November afternoon, and not wanting my spirits to become so depressed that I might begin to be affected by all sorts of morbid fancies, I was about to leave, and walk briskly back to the house, where I intended to switch on a good many lights and even light a small fire if it were possible, before beginning my preliminary work on Mrs. Drablow’s papers. But, as I turned away, I glanced once again round the burial ground and then I saw again the woman with the wasted face, who had been at Mrs. Drablow’s funeral. She was at the far end of the plot, close to one of the few upright headstones, and she wore the same clothing and bonnet, but it seemed to have slipped back so that I could make out her face a little more clearly.

In the grayness of the fading light, it had the sheen and pallor not of flesh so much as of bone itself. Earlier, when I had looked at her, although admittedly it had been scarcely more than a swift glance each time, I had not noticed any particular expression on her ravaged face, but then I had, after all, been entirely taken with the look of extreme illness. Now, however, as I stared at her, stared until my eyes ached in their sockets, stared in surprise and bewilderment at her presence, now I saw that her face did wear an expression. It was one of what I can only describe—and the words seem hopelessly inadequate to express what I saw—as a desperate, yearning malevolence; it was as though she were searching for something she wanted, needed—must have, more than life itself, and which had been taken from her. And, toward whoever had taken it she directed the purest evil and hatred and loathing, with all the force that was available to her. Her face, in its extreme pallor, her eyes, sunken but unnaturally bright, were burning with the concentration of passionate emotion which was within her and which streamed from her. Whether or not this hatred and malevolence was directed toward me I had no means of telling—I had no reason at all to suppose that it could possibly have been, but at that moment I was far from able to base my reactions upon reason and logic. For the combination of the peculiar, isolated place and the sudden appearance of the woman and the dreadfulness of her expression began to fill me with fear. Indeed, I had never in my life been so possessed by it, never known my knees to tremble and my flesh to creep, and then to turn cold as stone, never known my heart to give a great lurch, as if it would almost leap up into my dry mouth and then begin pounding in my chest like a hammer on an anvil, never known myself gripped and held fast by such dread and horror and apprehension of evil. It was as though I had become paralyzed. I could not bear to stay there, for fear, but nor had I any strength left in my body to turn and run away, and I was as certain as I had ever been of anything that, at any second, I would drop dead on that wretched patch of ground.

It was the woman who moved. She slipped behind the gravestone and, keeping close to the shadow of the wall, went through one of the broken gaps and out of sight.

The very second that she had gone, my nerve and the power of speech and movement, my very sense of life itself, came flooding back through me, my head cleared and, all at once, I was angry, yes, angry, with her for the emotion she had aroused in me, for causing me to experience such fear, and the anger led at once to determination, to follow her and stop her, and then to ask some questions and receive proper replies, to get to the bottom of it all.

I ran quickly and lightly over the short stretch of rough grass between the graves toward the gap in the wall, and came out almost on the edge of the estuary. At my feet, the grass gave way within a yard or two to sand, then shallow water. All around me the marshes and the flat salt dunes stretched away until they merged with the rising tide. I could see for miles. There was no sign at all of the woman in black, nor any place in which she could have concealed herself.

Who she was—or what—and how she had vanished, such questions I did not ask myself. I tried not to think about the matter at all but, with the very last of the energy that I could already feel draining out of me rapidly, I turned and began to run, to flee from the graveyard and the ruins and to put the woman at as great a distance behind as I possibly could. I concentrated everything upon my running, hearing only the thud of my own body on the grass, the escape of my own breath. And I did not look back.

By the time I reached the house again I was in a lather of sweat, from exertion and from the extremes of my emotions, and as I fumbled with the key my hand shook, so that I dropped it twice upon the step before managing at last to open the front door. Once inside, I slammed it shut behind me. The noise of it boomed through the house but, when the last reverberation had faded away, the place seemed to settle back into itself again and there was a great, seething silence. For a long time, I did not move from the dark, wood-paneled hall. I wanted company, and I had none, lights and warmth and a strong drink inside me, I needed reassurance. But, more than anything else, I needed an explanation. It is remarkable how powerful a force simple curiosity can be. I had never realized that before now. In spite of my intense fear and sense of shock, I was consumed with the desire to find out exactly who it was that I had seen, and how, I could not rest until I had settled the business, for all that, while out there, I had not dared to stay and make any investigations.

I did not believe in ghosts. Or rather, until this day, I had not done so, and whatever stories I had heard of them I had, like most rational, sensible young men, dismissed as nothing more than stories indeed. That certain people claimed to have a stronger than normal intuition of such things and that certain old places were said to be haunted, of course I was aware, but I would have been loath to admit that there could possibly be anything in it, even if presented with any evidence. And I had never had any evidence. It was remarkable, I had always thought, that ghostly apparitions and similar strange occurrences always seemed to be experienced at several removes, by someone who had known someone who had heard of it from someone they knew!

But out on the marshes just now, in the peculiar, fading light and desolation of that burial ground, I had seen a woman whose form was quite substantial and yet in some essential respect also, I had no doubt, ghostly. She had a ghostly pallor and a dreadful expression, she wore clothes that were out of keeping with the styles of the present-day; she had kept her distance from me and she had not spoken. Something emanating from her still, silent presence, in each case by a grave, had communicated itself to me so strongly that I had felt indescribable repulsion and fear. And she had appeared and then vanished in a way that surely no real, living, fleshly human being could possibly manage to do. And yet … she had not looked in any way—as I imagined the traditional “ghost” was supposed to do—transparent or vaporous, she had been real, she had been there, I had seen her quite clearly, I was certain that I could have gone up to her, addressed her, touched her.

I did not believe in ghosts.

What other explanation was there?

From somewhere in the dark recesses of the house, a clock began to strike, and it brought me out of my reverie. Shaking myself, I deliberately turne

d my mind from the matter of the woman in the graveyards, to the house in which I was now standing.

Off the hall ahead led a wide oak staircase and, on one side, a passage to what I took to be the kitchen and scullery. There were various other doors, all of them closed. I switched on the light in the hall but the bulb was very weak, and I thought it best to go through each of the rooms in turn and let in what daylight was left, before beginning any search for papers.

After what I had heard from Mr. Bentley and from other people once I had arrived, about the late Mrs. Drablow, I had had all sorts of wild imaginings about the state of her house. I had expected it, perhaps, to be a shrine to the memory of a past time, or to her youth, or to the memory of her husband of so short a time, like the house of poor Miss Havisham. Or else to be simply cobwebbed and filthy, with old newspapers, rags and rubbish piled in corners, all the débris of a recluse—together with some half-starved cat or dog.

But, as I began to wander in and out of morning room and drawing room, sitting room and dining room and study, I found nothing so dramatic or unpleasant, though it is true that there was that faintly damp, musty, sweet-sour smell everywhere about, that will arise in any house that has been shut up for some time, and particularly in one which, surrounded as this was on all sides by marsh and estuary, was bound to be permanently damp.

The furniture was old-fashioned but good, solid, dark, and it had been reasonably well looked after, though many of the rooms had clearly not been much used or perhaps even entered for years. Only a small parlor, at the far end of a narrow corridor off the hall, seemed to have been much lived in—probably it had been here that Mrs. Drablow had passed most of her days. In every room were glass-fronted cases full of books and, besides the books, there were heavy pictures, dull portraits and oil paintings of old houses. But my heart sank when, after sorting through the bunch of keys Mr. Bentley had given me, I found those which unlocked various desks, bureaux, and writing tables, for in all of them were bundles and boxes of papers—letters, receipts, legal documents, notebooks, tied with ribbon or string, and yellow with age. It looked as if Mrs. Drablow had never thrown away a single piece of paper or letter in her life, and, clearly, the task of sorting through these, even in a preliminary way, was far greater than I had anticipated. Most of it might turn out to be quite worthless and redundant, but all of it would have to be examined nevertheless, before anything that Mr. Bentley would have to deal with, pertaining to the disposal of the estate, could be packed up and sent to London. It was obvious that there would be little point in my making a start now, it was too late and I was too unnerved by the business in the graveyard. Instead, I simply went about the house looking in every room and finding nothing of much interest or elegance. Indeed, it was all curiously impersonal, the furniture, the decoration, the ornaments, assembled by someone with little individuality or taste, a dull, rather gloomy and rather unwelcoming home. It was remarkable and extraordinary in only one respect—its situation. From every window—and they were tall and wide in each room—there was a view of one aspect or other of the marshes and the estuary and the immensity of the sky, all color had been drained and blotted out of them now, the sun had set, the light was poor, there was no movement at all, no undulation of the water, and I could scarcely make out any break between land and water and sky. All was gray. I managed to let up every blind and to open one or two of the windows. The wind had dropped altogether, there was no sound save the faintest, softest suck of water as the tide crept in. How one old woman had endured day after day, night after night, of isolation in this house, let alone for so many years, I could not conceive. I should have gone mad—indeed, I intended to work every possible minute without a pause to get through the papers and be done. And yet, there was a strange fascination in looking out over the wild wide marshes, for they had an uncanny beauty, even now, in the gray twilight. There was nothing whatsoever to see for mile after mile and yet I could not take my eyes away. But for today I had had enough. Enough of solitude and no sound save the water and the moaning wind and the melancholy calls of the birds, enough of monotonous grayness, enough of this gloomy old house. And, as it would be at least another hour before Keckwick would return in the pony trap, I decided that I would stir myself and put the place behind me. A good brisk walk would shake me up and put me in good heart, and work up my appetite and if I stepped out well I would arrive back in Crythin Gifford in time to save Keckwick from turning out. Even if I did not, I should meet him on the way. The causeway was still visible, the roads back were straight and I could not possibly lose myself.

So thinking, I closed up the windows and drew the blinds again and left Eel Marsh House to itself in the declining November light.

The Sound of a Pony and Trap

Outside, all was quiet, so that all I heard was the sound of my own footsteps as I began to walk briskly across the gravel, and even this sound was softened the moment I struck out over the grass toward the causeway path. Across the sky, a few last gulls went flying home. Once or twice, I glanced over my shoulder, half expecting to catch sight of the black figure of the woman following me. But I had almost persuaded myself now that there must have been some slope or dip in the ground upon the other side of that graveyard and beyond it, perhaps a lonely dwelling, tucked down out of sight, for the changes of light in such a place can play all manner of tricks and, after all, I had not actually gone out there to search for her hiding place, I had only glanced around and seen nothing. Well, then. For the time being I allowed myself to remain forgetful of the extreme reaction of Mr. Jerome to my mentioning the woman that morning.

On the causeway path it was still quite dry underfoot but to my left I saw that the water had begun to seep nearer, quite silent, quite slow. I wondered how deeply the path went under water when the tide was at height. But, on a still night such as this, there was plenty of time to cross in safety, though the distance was greater, now I was traversing it on foot, than it had seemed when we trotted over in Keckwick’s pony cart, and the end of the causeway path seemed to be receding into the grayness ahead. I had never been quite so alone, nor felt quite so small and insignificant in a vast landscape before, and I fell into a not unpleasant brooding, philosophical frame of mind, struck by the absolute indifference of water and sky to my presence.

Some minutes later, I could not tell how many, I came out of my reverie, to realize that I could no longer see very far in front of me and when I turned around I was startled to find that Eel Marsh House, too, was invisible, not because the darkness of evening had fallen, but because of a thick, damp sea-mist that had come rolling over the marshes and enveloped everything, myself, the house behind me, the end of the causeway path and the countryside ahead. It was a mist like a damp, clinging cobwebby thing, fine and yet impenetrable. It smelled and tasted quite different from the yellow filthy fog of London; that was choking and thick and still, this was salty, light and pale and moving in front of my eyes all the time. I felt confused, teased by it, as though it were made up of millions of live fingers that crept over me, hung on me and then shifted away again. My hair and face and the sleeves of my coat were already damp with a veil of moisture. Above all, it was the suddenness of it that had so unnerved and disorientated me.

For a short time, I walked slowly on, determined to stick to my path until I came out onto the safety of the country road. But it began to dawn upon me that I should as likely as not become very quickly lost once I had left the straightness of the causeway, and might wander all night in exhaustion. The most obvious and sensible course was to turn and retrace my steps the few hundred yards I had come and to wait at the house until either the mist cleared, or Keckwick arrived to fetch me, or both.

That walk back was a nightmare. I was obliged to go step by slow step, for fear of veering off onto the marsh, and then into the rising water. If I looked up or around me, I was at once baffled by the moving, shifting mist, and so on I stumbled, praying to reach the house, which was farther away than I had imagin

ed. Then, somewhere away in the swirling mist and dark, I heard the sound that lifted my heart, the distant but unmistakable clip-clop of the pony’s hooves and the rumble and creak of the trap. So Keckwick was unperturbed by the mist, quite used to traveling through the lanes and across the causeway in darkness, and I stopped and waited to see a lantern—for surely he must carry one—and half wondered whether to shout and make my presence known, in case he came suddenly upon me and ran me down into the ditch.

Then I realized that the mist played tricks with sound as well as sight, for not only did the noise of the trap stay further away from me for longer than I might have expected but also it seemed to come not from directly behind me, straight down the causeway path, but instead to be away to my right, out on the marsh. I tried to work out the direction of the wind but there was none. I turned around but then the sound began to recede further away again. Baffled, I stood and waited, straining to listen through the mist. What I heard next chilled and horrified me, even though I could neither understand nor account for it. The noise of the pony trap grew fainter and then stopped abruptly and away on the marsh was a curious draining, sucking, churning sound, which went on, together with the shrill neighing and whinnying of a horse in panic, and then I heard another cry, a shout, a terrified sobbing—it was hard to decipher—but with horror I realized that it came from a child, a young child. I stood absolutely helpless in the mist that clouded me and everything from my sight, almost weeping in an agony of fear and frustration, and I knew that I was hearing, beyond any doubt, appalling last noises of a pony and trap, carrying a child in it, as well as whatever adult—presumably Keckwick—was driving and was even now struggling desperately. It had somehow lost the causeway path and fallen into the marshes and was being dragged under by the quicksand and the pull of the incoming tide.

Mrs De Winter

Mrs De Winter A Question of Identity

A Question of Identity The Various Haunts of Men

The Various Haunts of Men The Pure in Heart

The Pure in Heart Printer's Devil Court

Printer's Devil Court The Travelling Bag

The Travelling Bag The Risk of Darkness

The Risk of Darkness A Kind Man

A Kind Man Black Sheep

Black Sheep The Betrayal of Trust

The Betrayal of Trust The Service of Clouds

The Service of Clouds Betrayal of Trust

Betrayal of Trust The Small Hand

The Small Hand Dolly

Dolly Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading

Jacob's Room Is Full of Books: A Year of Reading The Vows of Silence

The Vows of Silence The Soul of Discretion

The Soul of Discretion The Shadows in the Street

The Shadows in the Street The Man in the Picture

The Man in the Picture Air and Angels

Air and Angels Strange Meeting

Strange Meeting In the Springtime of the Year

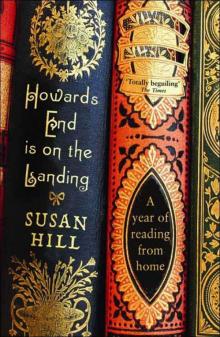

In the Springtime of the Year Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home

Howards End Is on the Landing: A Year of Reading From Home From the Heart

From the Heart Old Haunts

Old Haunts The Mist in the Mirror

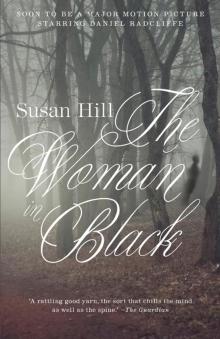

The Mist in the Mirror The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story

The Woman in Black: A Ghost Story A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7)

A Question of Identity (Simon Serrailler 7) The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home Mist in the Mirror

Mist in the Mirror Jacob's Room is Full of Books

Jacob's Room is Full of Books The Woman in Black

The Woman in Black Howards End is on the Landing

Howards End is on the Landing